The Image of Security Sector Agencies as a Strategic Communication Tool

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 16, Issue 3, p.5-22 (2017)Keywords:

discourse, image formation, image reparation, security sector agency, strategic communication, strategy.Abstract:

This article highlights the corporate image as a strategic communication tool for security sector agencies. The prospects of image for a security sector agency are outlined with regard to image formation and reparation. Image formation is based on the principles of objectivity, openness, credibility and trust whilst avoiding deception and manipulation. Best practices and failures in image formation are listed from the U.S. and Ukrainian security sector agencies’ experience. The suggested guidance on image formation for security sector agencies encompasses the author’s recommendations on effective image formative discourse and the corresponding institutional policy development.

Introduction

The hybrid character of modern warfare features a drastic shift when force employment strategies become appendices to information and communication strategies.[1] Taking into account the parallel developments in warfare and communication, the “strategic communication community can learn a great deal from Clausewitz and from current attempts in military theory to make sense from what is currently happening in strategic communication.” [2]

The image of security sector agencies is a powerful tool of hybrid wars in the information and communication domain. Within a global war scenario, image is regarded as a weapon for shooting the agency’s discourse with the desirable precision, accuracy, rate and volume. The image of security sector agencies is effectively used to target the audience’s mind and way of thinking in wartime, as well as in peacetime.

This article aims at determining the corporate image frame as a strategic communication tool for security sector agencies and outlining best practices for the image formation of security sector agencies. From the multifaceted perspective of strategic communication in general, it addresses the communicative aspects of image that influence the capability of security sector agencies.

The underlying study is multidisciplinary and is at the intersection of several social and human sciences: philosophy, imageology, communicative linguistics, cognitive science, media linguistics, discourse studies and sociolinguistics. This synergistic nature results in the need to address different types of sources for a comprehensive literature review on the subject, the outline of best practices in the military and law-enforcement image formation and the construction of an image frame in the strategic communication of a security sector agency.

Strategic Communication in the Security Sector

Essence of Strategic Communication

Strategic communication gained special popularity in business, political and military domains in the second decade of the XXI century, and as a relatively new term, it still gives rise to discussions on its essence, scope and functions.

For the purpose of this research, the definition by Holtzhausen and Zerfass was chosen for the reason that it emphasizes the public sphere: “Strategic communication is the practice of deliberate and purposive communication that a communication agent enacts in the public sphere on behalf of a communicative entity to reach set goals.” [3]

The NATO Strategic Communications concept is designed to ensure that audiences receive clear, fair and opportune information regarding actions and that the interpretation of the Alliance’s messages is not left solely to NATO’s adversaries or other audiences.[4]

It is necessary to mention, that in September 2009 NATO developed its Policy on Strategic Communication to respond to “today’s information environment” that “directly affects how NATO actions are perceived by key audiences,” owing to the fact “that perception is always relevant to, and can have a direct effect on the success of NATO operations and policies.” [5] Thus, an audience’s impression of NATO, in other words its image, was the major concern for this policy development. This point of view concurs with the business vision of strategic communication, since “the aim of strategic communication is to maintain a healthy reputation for the communicative entity in the public sphere.” [6]

In this respect, it is essential to underline that strategic communication is rather about influence strategies with the perception of the organization as the outcome, not merely media and information as the channel and content, when “one or a combination of variables (i.e., message source, message itself, message channel, and message recipient) can lead to cognitive and behavioral changes.” [7]

Strategic communication is vitally important nowadays for any security sector agency in any country. StratCom departments and/or other structures responsible for strategic communication have been established in practically every agency. In 2013 NATO launched its Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence in Riga, Latvia. The “Defence Strategic Communications” journal aims to bring together military, academic, business and governmental knowledge. It is a norm of our information age for security sector agencies to maintain their websites, have their own media and profiles on social networks.

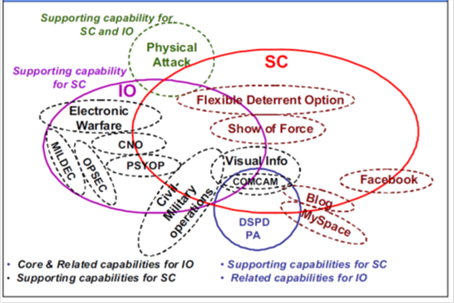

Recognizing the lack of doctrinal guidance, the U.S. Joint Forces Command composed and later updated its pre-doctrinal “Commander’s Handbook for Strategic Communication and Communication Strategy” in order “to help joint force commanders and their staffs understand alternative perspectives, techniques, procedures, ‘best practices,’ and organizational options.” [8] This Commander’s Handbook contains a comprehensive analysis of military capabilities related to information and communication (Figure 1).

There are several basic principles of strategic communication for the communicator:

· Building healthy professional relations with the media

· Recognizing the diversity of the media and choice factors for the media as the communication channels

Figure 1: Strategic Communication Relationships.[9]

Figure 1: Strategic Communication Relationships.[9]

· Composing a message in congruity with the agency’s discourse

· Addressing the message to the target audience with regard to collateral and/or “eavesdropping” audiences

· Using factual information without lying, deception or speculation.

Strategic communication includes strategic narratives that are “intended to help people make sense of events related to the use of military force in ways that are likely to give rise to a particular feeling or opinion.” [10] The narrative is understood as “a story explaining an actor’s actions in order to justify them to his/her audience. The aim of a narrative is to guide decisions so as to ensure their coherence. It acts as an institution’s brand.” [11] In the empirical research findings, it is stated that “to be effective, narratives must both resonate with the intended audience’s core values and advocate a persuasive cause-effect description that ties events together in an explanatory framework.” [12]

Strong strategic narratives are characterized by four basic elements [13]:

· They articulate a clear and compelling mission purpose

· They hold the promise of wartime success

· They must be coherent and consistent

· They are characterized by having few and/or weak competitors.

Strategic Communication, Propaganda and Counter-Propaganda

Nowadays, strategic communication is differentiated from propaganda and counter-propaganda by the means and methods perspective. Strategic communication is based on the classic definition of ‘propaganda’—using factual, and accurate information—though “the word ‘propaganda’ itself, however, has taken on too much baggage over the last century to be useful in today’s context.” [14] In WWII, propaganda became a powerful weapon in the Nazi arsenal and was developed into the ‘Big Lie’ technique. Subsequently, the term itself was compromised and became a synonym for lies and deception.

With its ultimate aim to influence the target audience and encourage it into action by providing the truthful ‘why’ information, strategic communication does not, or rather should not, use the propaganda tools of disinformation and manipulation, as it might have the opposite effect – loss of credibility and trust. For instance, NATO Strategic Communication is meant to coordinate all information and communication capabilities and this could not be done if the concept referred to deception: deception is only allowed in certain military capabilities, and not by all in every country.[15]

Strategic communication does not include counter-propaganda since the latter tends to use the same means as propaganda. For example, counter-propaganda in Ukraine is regarded as energy- and cost-ineffective when it comes to modern information wars: “The biggest mistake that we could make, the biggest mistake that Ukraine could make, is to spend all of your time and all of your energy trying to counter the lies /… /.” [16]Ambassador Pyatt believes that Ukraine’s initiative to control the information flow and ‘mirroring’ current propaganda fails:

It’s a huge mistake for the Ukrainian government, for the Ukrainian people, to create a troll factory like St. Petersburg, churning out counter-propaganda in social media. It’s a huge mistake to create a ‘Ministry of Truth’ [Ministry of Information of Ukraine] that tries to generate alternative stories because Ukraine doesn’t need more propaganda machine, it needs more objective information.[17]

Strategic communication in itself is not a universal remedy to ensure a security sector agency’s success and positive attitudes in the society. “Positive and credible narratives build population’s resilience against hostilities. Holding that credibility requires that the deeds match the words.” [18]

Prospects of Image for a Security Sector Agency

Essence of Image

The image of a security sector agency is the audience’s impression of this organization that is rooted in the mass and/or individual consciousness.[19] Image forms and develops as a result of processing the external information of this agency and its activity through the net of current stereotypes. Image is socially biased. Image is linked to reputation, the latter being based on the agency’s previous activity, and image being a social perception of the agency, based on attitudes, stereotypes and information obtained from outside. Thus, image is a social construct grounded on the audience’s interpretation and attitudes.

Image corresponds to the audience’s stereotypical and prototypical ideas on the agency as it should be, and it is able to substitute the agency or/and represent the agency in the audience’s perception.

Image is a valuable tool in raising the respect of the agency that leads to sustainability and social development. Public support is crucial for security sector reform and depends not only on the reforms themselves, but on the public perception, grounded on the agency’s discourse and mass-media coverage of this process and security sector activity in general.

Image is the agency’s communication tool which influences the audience’s perception of the agency’s discourse. At the same time, image is shaped by this discourse among the others.

Image Formation Process

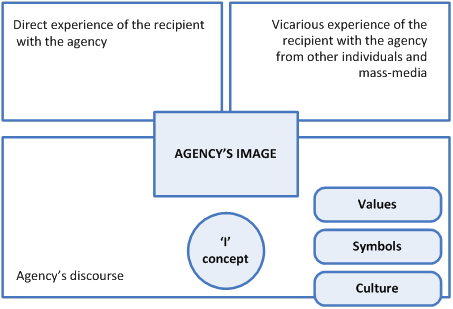

The image of a security sector agency is shaped by direct experience with the agency and by the vicarious experience from what others (individuals, mass-

Figure 2: Communication Domains of Security Sector Agency’s Image Formation.

media and other communication means) say regarding the agency. Taking into account that incomplete knowledge and/or corrupt messages can damage the image; the agency must fill the communication space with its discourse. Thus, there are three main domains in which the image of a security sector agency is being formed (Figure 2):

· direct experience of the recipient with the agency

· vicarious experience of the recipient with the agency from other individuals and mass-media

· the agency’s discourse (web sites, media, press-conferences etc.).

Image is formed explicitly and implicitly. Every media message on the military or law-enforcement contains an image formative aspect. Thus, positive image formation should be based on the strategy as a plan of communicative influence on the recipient.

To influence the image formative process, the agency must model the image core element – its ‘I’ concept, which is a compromise between ‘real ME’ and ‘ideal ME.’ The desirable image for a security sector agency is the reduction of the discrepancy between the ‘I’ concept and the audience’s attitude to this agency. The agency’s leadership is responsible for outlining the ‘I’ concept. Then, appropriate image formative symbols and concepts are chosen to verbalize the desirable image, and this model is placed into real contexts in the form of the agency’s discourse. This is done by communicators – departments or individuals responsible for the agency’s strategic communication.

The agency’s discourse is the domain that the communicator can control and where he/she can verbalize the ‘I’ concept and ingrain the agency’s values, symbols and culture. If this domain is properly maintained, it influences the other two and builds a filter in the consciousness of the target audience for perceiving the external information regarding the agency. This filter might be strong enough to block any negative information of the agency’s ‘wrong-doing.’ In fact, this filter corresponds to Lakoff’s frame theory, “frames being mental structures shaping the way we see the world.” [20] According to Lakoff:

Framing is critical because a frame, once established in the mind of the reader (or listener, viewer, etc.), leads that person almost inevitably to the conclusion desired by the framer, and it blocks consideration of other possible facts and interpretations.[21]

Based on cognitive and pragmatic analysis of research material, the author suggests an image formative communicative strategies taxonomy (Table 1) built on:

· the content of the desirable image of a security sector agency,

· object-space features of this image

· the sender’s intention that conditions the strategy and tactics choice

· linguistic means for these tactics realizations.

Table 1: Taxonomy of Image Strategies.

Stage | Goal | Essence | Strategy options |

Image formation | Affirmation | Initiating an image | · Appeal to common values · Self-introduction |

Image enhancement/ enforcement | Reaffirmation | Revitalizing an image | · Appeal to common values · Presentation of the activities |

Image reparation | Purification | Correcting an image | · Legitimation of actions · Mitigation · Face-work |

Image damage | Subversion | Undermining an image | · Discredit · Discrimination · Defamation |

The image strategies are flexible and can be realized by a number of communicative tactics. Appeal to common values includes the values of any security sector agency (Service), nation (Integrity, Patriotism), and society (Excellence, the Truth).

Image Reparation Strategies

The latest news and analytical publications in mass-media (July 2016: Police shooting in the USA, French police failure to prevent the terroristic act in Nice) prove a wide need to repair the image of these agencies in order to restore the trust of society and to enhance cooperation. W. L. Benoit states that “a damaged reputation can hurt our persuasiveness because credibility generally and trustworthiness in particular are important to persuasion.” [22] Negative image contains two main components: responsibility and offensiveness.

Within image repair theory, it is believed that threats to an image are inevitable for at least four reasons [23]:

· Our world has limited resources

· Events are out of control and sometimes keep us from meeting our obligations

· Sometimes we commit misdeeds, make honest errors, or allow our behavior to be guided too much by our self-interests

· The fact that we are individuals with different priorities can create conflict arising from our competing goals.

The agency must decide on the threats and whether to address them or not. Trivial accusations do not need to be addressed while “it is a mistake to ignore an important accusation.” [24] The attacks are significant to the agency when they are believed to damage the agency’s reputation “in the eyes of the group or the audience who is salient to the source.” [25]

As communication has a potential to repair the damaged image, image reparation is intended to improve it and to reshape the audience’s attitudes. There are two key assumptions here: communication is a goal-oriented activity, and maintaining a positive reputation is one of the central goals of communication.[26] The main communicative strategies for image reparation are summarized in Table 2. It is necessary to note, that image reparation discourse is included in a wider crisis communication along with other images with respect to other kinds of crises.

Table 2: Image Reparation Strategies.

Strategy | Addressed Component | Goal | Strategy options |

Challenging blame or offensiveness | Responsibility | Rejecting blame, mitigation | · Denying responsibility · Shifting blame to others · Reducing responsibility · Good intentions |

Offensiveness | Reducing perceived offensiveness of the action | · Bolstering · Minimization · Differentiation · Transcendence · Attack Accuser · Compensation | |

Admitting wrong-doing |

|

| · Asking for forgiveness · Promising to fix the problem |

Denial |

|

| · Simple denial · Shift the blame |

The recipient of an image reparation message is defined based on the image damaging agent and the target audience of the image damaging message or attack that the agency is concerned about. The agency might need to repair its reputation with the image damaging agent, or with the image damaging agent and a wider target audience, or with the audience neglecting the image damaging agent.

Image of Security Sector Agencies: Best Practices and Failures

Nowadays, Ukraine’s Armed Forces and National Guard struggle to form a positive image in order to win the support of society. Different channels are used, including national mass media, official websites and social media. Mass media and social media monitoring shows that some of the steps undertaken in this direction are effective, others lead to misunderstanding and bring more harm to the general perception of these agencies. It is crucial to know what to tell and how to tell it, how to promote corporate values, how to present information on the reform process, etc. “Actual policy counts at least as much as how something is framed.” [27] All this belongs to strategic communication.

For the purpose of this research, several best practices and obvious failures are examined:

Public Opinion Polling, Surveying and Focus Groups

Feedback is what any agency’s communicator needs to evaluate and validate his/her image formative strategy in order to improve or to change it. In 2003, the Center for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) in Geneva built a wide picture of the public image of security, defense and the military in Europe [28] based on public opinion polls and surveys. This publication, of course, does not reflect the current situation since many things have changed in the last 13 years; it rather highlights the necessity and usefulness of comprehensive opinion polls. Whilst such polls (as well as focus groups and discussions) are expensive, they can be substituted by Internet surveys that can give at least an idea of the agency’s image.

Embedded Reporters

One of the practices to communicate a positive image of the military to a wider audience is to use the so called “embedded reporters” – media representatives getting their “boots on the ground” experience with the troops in order to share it with their audience. Earlier in Iraq and later in Ukraine, the audience got a first-hand perspective of military life with the deployed U.S. troops and Ukraine’s Armed Forces. The U.S. experience showed that “even if the stories do not gain strong nationwide coverage, they do gain good regional coverage and, in many cases, this regional coverage is more appropriate.” [29] The efficiency of “embedded reporters” depends on the reporters’ credibility and the trustworthiness of the message.

Police as Newsmakers

The image of security sector agencies in the USA is rather positive; the military are treated with respect by the public. At the same time, the 2014 clashes in Ferguson animated a debate regarding law enforcement’s relationship with African Americans, and the use of force by the police. Mass-media played a great role in presenting the facts and forming the attitudes of the audience to the unrest and to the police in general.

In recent police shootings in the USA, police officers did not take responsibility for the shooting of two men and these shootings appear to have angered the African American population of the country. Understanding both responsibility and offensiveness for the accusation, the Chief of Baton Rouge Police Department produced a press conference statement [30] – a classical image reparation message containing the following key elements:

· acknowledgement of responsibility, including a personal demand for an investigation

· a reaction to the police officers involved: suspension, leave

· mitigation of the blame: 911 call reaction

· call for a transparent, independent investigation

· appeal to the authorities: calling in the U.S. Attorney, and the FBI

· an invitation for collaboration to guarantee a just investigation, and a plea for understanding.

This press conference was an attempt to break the rhythm of the negative story development. But it failed, as well as several others on the police department Facebook page. Unfortunately, the previously formed negative image had not been repaired. Consequently, the U.S. police were still connected to indiscriminate violence and the shooting of African Americans which became a fertile soil for implementing the conceptual opposition “WE vs. THEY” in the form of “POLICE vs. AFRICAN AMERICANS.” This conflict acquired additional impetus with the #BlackLivesMatter movement organized in 2013, and multiple democratic protests. The “POLICE vs. AFRICAN AMERICANS” opposition grew into a racial issue and led to actions against the police when eight police officers were killed in ten days.

It is probable that the situation was aggravated and went out of control owing to the negative image of the U.S. police which negated the agency’s discourse being perceived by the audience as a means of resolving the conflict.

Correct Wording

The success of a security sector agency’s image formation, as well as the efficacy of the agency’s strategic communication, depends on the choice of the main concepts for the discourse and their specific verbalization in different contexts for different audiences. For instance, in 1993, Luntz advised Rudy Giuliani to avoid the words ‘crime’ and ‘criminals.’ He maintained that “the public placed a higher priority on “personal and public safety” than on “fighting crime” (rather procedural) or even “getting tough on criminals” (rather punitive), while ‘safety,’ although somewhat abstract, is definitely personal, and most of all aspirational – the ultimate value and the desired result of an effort to fight crime.[31] Giuliani’s success in New York City influenced the American way of thinking in this respect, shifting from an emphasis on ‘crime’ to “safe, civil society.”

Rebranding

Rebranding is a marketing tool and is initiated with serious reasons in mind. Rebranding in the security sector is done when the agency’s image cannot be repaired or when restoration is required on a constant basis. For instance, Ukraine, as well as several other countries in the area, inherited “interior troops” from the former USSR. Having such a formation within the country gave rise to many questions, like “Fighting against whom within the country? Against people?” The reputation and image of this military formation was spoiled completely after the clashes between Maidan protesters and these law-enforcement agencies in winter 2013-2014. The subsequent rebranding campaign was meant to be a reconciliation between the National Guard and the general public using the motto “new and improved.” However, given the strict time constraints and limited funds, the National Guard of Ukraine did not have a comprehensive strategy for rebranding based on mission, vision and values. Consequently, the process of re-establishing the National Guard of Ukraine turned out to be long, unstructured and chaotic with internal cultural conflicts, and the need for significant image reparation along the way.

Joint Effort

In order to be successful, the image formative process needs to be coordinated and intensive. This statement can be illustrated by the image campaign aligned with the creation of a rapid reaction brigade of the National Guard of Ukraine in 2015-2016. The image campaign used all the instruments of strategic communication available:

· numerous messages with a positive connotation in the media, along with boastful messages on the agency’s official site and media

· informative speeches by the Commander of the National Guard of Ukraine

· topical press-conferences and interviews with leaders of different levels

· positive evaluation notes from the President of Ukraine

· appraisal quotes from world military authorities, e.g. General Hodges.

As a result of this image campaign, the rapid reaction brigade now has a positive image within society, it attracts special attention and is a symbol of effective reform in the security sector of Ukraine.

Guidance on Image Formation for Security Sector Agencies

For the purpose of this study, one can follow two main directions for guidance on image formation for security sector agencies: effective image formative discourse and policy development.

Effective Image Formative Discourse

This section of the guidance is rather tactical, and has been composed for the communicators who are exercising strategic communication.

Recipient’s Factor

From a pragmatic perspective, the recipient’s factor is the most significant for strategic communication since “it is not what you say, it is what people hear.” [32] Correspondingly, image formation depends on the recipient, too. Moreover, the recipient owns all the images shaped in his/her consciousness. Thus, all strategic communication messages should be composed with regard to the target audience’s variables: age, gender, occupation, life experience, education and assumptions. Even rhetorical skills nowadays are not only about speech, they are about recognizing social circumstances and grasping what the audience expects.[33] An ideal message must bring some personal meaning and values to the recipient. For example, women generally respond better to stories, anecdotes and metaphors, while men are more fact-oriented and statistical.[34] Taking into account that young people read less, image messages should be short with a catchy beginning and end.

Values

Values constitute the basis for a security sector agency’s image formation. The agency’s values shouldn’t contradict the values of a nation or a society. Any discrepancy in value systems can lead to a potential conflict. The choice of the value concepts depends on the agency’s mission and vision. Usually, the agency’s values are scrupulously formulated as a sound set of concepts. For instance, the Seven Core U.S. Army Values are Loyalty, Duty, Respect, Selfless Service, Honor, Integrity and Personal Courage.[35] The values of the National Guard of Ukraine are Honor, Courage and, Law.[36]

Image of the Leader

To a certain extent, the image discourse of a security sector agency is determined by the leader’s personality. It is not only that the leader formulates the agency’s vision, it is that the leader personifies the agency. The audience tends to form attitudes based on the leader’s attributes, thus the requirement for the leader is to have a strong communication personality. At the same time, “messengers who are their own best message are always true to themselves.” [37] There are examples when leaders are exaggeratedly public, preferring to communicate intensively to the audience via social media. It is an art for a leader to find a necessary balance, but openness usually contributes to an agency’s positive image. It presupposes that the leader will participate in press-conferences, interviews, image events, etc.

Message

Content, structure and function are of special importance for a good message. As with any strategic communication, an image formative message is persuasive in its nature. The results of earlier surveys show that persuading and informing are the two primary functions of a strategic communication message out of the six identified by Hazleton: facilitate, inform, persuade, coerce, bargain, and solve problems. Persuasive strategies produced the highest level of involvement among the general public.[38] For example, a “persuasive framing of the use of military power can thus, to some extent, immunise or shield public opinion against the conventional effects of a rising number of casualties.” [39]

For a message to be persuasive, special attention should be given to the structure. Framing a message to provide context and relevance, depends on a number of factors such as the recipient, the channel, the time and the topic. What has proven to be effective is to “give context ‘why’ before ‘so that’ and ‘how,’ because the order in which you present information determines context, and it can be as important as the substance of the information itself.” [40] For instance, messages with information on an agency’s ‘wrong-doing’ should have a sandwich structure such as: a positive fact regarding the agency or a general security environment—the negative information which is the core of this message—another positive fact regarding the agency or further steps to be taken. These findings correspond to an essential language rule that contradicts the logics: “A+B+C does not necessarily equal C+B+A.” [41]

Message persuasiveness is not reached solely by rational arguments and facts. The emotional component can be dominant for many audiences. The personalization and humanization of a message can help to trigger an emotional remembrance.[42]

Proceeding from the statement that if “you want to reach the people, you must first speak their language,” [43] “the Ten Rules of effective language” [44] are applicable for image formative messages: Simplicity, Brevity, Credibility, Consistency, Novelty, Sound, Aspiration, Visualization, Questioning, and Context.

The image formative message content is conveyed by language and visual means. The visual means are gradually acquiring more significance owing to the younger generation’s kaleidoscopic picture of the world which is the result of the shift in our thinking towards the ‘clip’ style of presentation. Visuals are widely used to support security sector agencies discourse. A short motto ‘Aim High’ on the official site of the U.S. Air Force Recruiting [45] is endorsed by an exciting video aimed at the emotional sphere of the recipient.

Image formative messages can be rolled into mottoes and slogans. The quality dimension for a message prevails the quantitative one. The main requirement is that successful, effective messages stick in our brains and never leave, and they also move people to action.[46]

Consistency and Coherency of Image Formative Discourse

Consistency and coherency are related to the recipient factor as they are linked to the audience diversity. Coherency is not a linear feature. Messages need to be different for different audiences. Instead of the same ‘universal’ message distribution via different channels, the image formative messages, as well as the agency’s discourse in general, represent a wide range of diverse messages on the same topic for different contexts and different audiences. The point here is that these messages should be consistent, coordinated, coherent and mutually reinforcing.

Policy Development on Security Sector Agency’s Image Formation and Reparation

Strategic communication is regarded as an integral function, rather than an adjunct to the planning and conduct of all military operations and activities. It is also a command and a control process to ensure operational success and alliance cohesion.[47] The research “Mapping of StratCom practices in NATO countries” shows that:

StratCom is still a long way from being a supported—rather than supporting—capability, since for communications to sit at the heart of strategy, there is a strong demand for clear ‘top down’ direction at the military and political level.[48]

Image potential to increase the organization or agencies capability is not explicitly recognized in the existing strategic communication policies. For instance, image is not included in the NATO Policy on Strategic Communications, but among the six key principles “soliciting public views” is mentioned [49] which indirectly refers to image.

Proceeding from the role of image for a security sector agency’s strategic communication and the necessity of ‘top-down’ initiative, the following points might be considered with regard to the National Guard of Ukraine:

· The need to develop a strategic communication policy or doctrine. This initiative may result in a separate doctrine or a plan that states the key elements of the desired image to be communicated to different audiences:

o The agency’s vision, mission and values developed on the basis of the agency’s mandate

o The communicator’s role, structure, rights and responsibilities.

· A requirement to conduct a SWOT analysis (strength, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) of the agency’s image on a regular basis in order to monitor the situation and enforce the image consistency with the ‘I’ concept.

· Preparing contingency plans to anticipate potential threats to the image and “prepare responses without stress and time pressure.” [50] Based on the contingency plans, to generate standard messages as responses to the anticipated threats. “In a crisis, these plans should be adapted to the specific situation and implemented thoughtfully, not followed blindly. Furthermore, crisis response plans should be reviewed periodically and revised or updated as appropriate.” [51]

Conclusion

Strategic communication is an umbrella term for a wide scope of a security sector agency’s communications, including discourse and actions. Within a security sector, strategic communication applies to all existing information and communication capabilities, and it is not limited to media activities. As strategic communication is directed towards “winning hearts and minds,” [52] the image of a security sector agency becomes a crucial tool in this endeavor as it contributes to the recipient’s attitudes to this agency, his/her behavior and support actions.

The image of a security sector agency is a social construct grounded on the audience’s perception, interpretation and attitudes. Shaped in strategic communication, it functions as a filter in the recipient’s consciousness for receiving external information concerning the agency.

For a security sector agency, image formation is a comprehensive process, supported by a corresponding policy or doctrine that states the agency’s ‘I’ concept with the values indicated. The communicator in charge of the image formation process develops the agency’s discourse in conformity with the policy, monitors the image realization in real contexts and introduces modifications to enforce or repair the image when necessary.

As a tool of strategic communication, image formation is based on the same principles of objectivity, openness, credibility and trust, avoiding deception and manipulation. Though, there is always a possibility that the security sector agency’s image may be misused by the agency and the media. Further research into the problem may be able to identify the mechanism of bilateral shaping between image formation and strategic communication in the security sector and its opportunities and threats.

About the Author

Dr. Iryna Lysychkina is Associate Professor, Chair of the Department of Philology, Translation and Lingual Communication at the National Academy of the National Guard of Ukraine, Kharkiv, Ukraine.

[1] Anaïs Reding, Kristin Weed, and Jeremy J. Ghez, NATO’s Strategic Communications Concept and its Relevance for France, Prepared for the Joint Forces Centre for Concept Development, Doctrine and Experimentation, France (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2010), 4.

[2] Simon M. Torp, “The Strategic Turn in Communication Science: On the History and Role of Strategy in Communication Science from Ancient Greece,” in The Routledge Handbook of Strategic Communication, ed. Derina Holtzhausen and Ansgar Zerfass, (New York, London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2015), 24.

[3] Derina Holtzhausen and Ansgar Zerfass, “Strategic Communication: Opportunities and Challenges of the Research Area,” in The Routledge Handbook of Strategic Communication, 74.

[4] PO(2009)0141, cited via Reding and Weed, “NATO’s Strategic Communications,” 4.

[5] NATO Policy on Strategic Communications, SG(2009)0794, 1.

[6] Holtzhausen and Zerfass, “Strategic Communication,” 5.

[7] Kenneth E. Kim, “Framing as a Strategic Persuasive Message Tactic,” in The Routledge Handbook of Strategic Communication, 285.

[8] Commander’s Handbook for Strategic Communication and Communication Strategy, Version 3 (Suffolk, VA: US Joint Forces Command, Joint Warfighting Center, 2010).

[9] Commander’s Handbook.

[10] Andreas Antoniades, Ben O’Loughlin, and Alister Miskimmon, “Great Power Politics and Strategic Narratives,” Working Paper No. 7 (2010), The Centre for Global Political Economy, University of Sussex, accessed August 3, 2016. doi: 10.4324/9781315770734.

[11] Reding, Weed, and Ghez, “NATO’s Strategic Communications,” X.

[12] Antoniades, O’Loughlin, and Miskimmon, “Great Power Politics,” 5.

[13] Jens Ringsmose and Berit K. Børgesen, “Shaping public attitudes towards the deployment of military power: NATO, Afghanistan and the use of strategic narratives,” European Security 20, no. 4 (2011): 505-528, accessed August 3, 2016. doi:10.1080/ 09662839.2011.617368, 513-514.

[14] Richard Halloran, “Strategic Communication,” Parameters 37 (Autumn 2007): 4-14, accessed August 3, 2016, http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/Articles/07autumn/halloran.pdf, 6.

[15] Reding and Weed, “NATO’s Strategic Communications”, 12.

[16] Geoffrey Pyatt, Remarks by Ambassador Pyatt at the “Countering Information War in Ukraine,” Conference, January 29, 2016. In: Speeches and Interviews by Ambassador Geoffrey R. Pyatt – Embassy of the USA in Ukraine, accessed August 3, 2016, http://ukraine.usembassy.gov/speeches/pyatt-01292016.html.

[17] Pyatt, Remarks by Ambassador Pyatt.

[18] Antti Sillanpää, “Strategic communications and need for societal narratives” (paper presented at The Riga Conference 2015, Riga, November 13, 2015), accessed August 3, 2016, https://www.rigaconference.lv/rc-views/22/strategic-communications-and-need-for-societal-narratives.

[19] Alexey Olianich, Presentational Theory of Discourse [Prezentacionnaya teoria diskursa] (Moscow: Gnosis, 2007), 107.

[20] George Lakoff, The ALL NEW Don't Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2014), xv.

[21] Lakoff, The ALL NEW Don't Think of an Elephant!, 8.

[22] William L. Benoit, “Image Repair Theory in the Context of Strategic Communication,” in The Routledge Handbook of Strategic Communication, 304.

[23] Benoit, “Image Repair Theory,” 303.

[24] Benoit, “Image Repair Theory,” 305.

[25] Benoit, “Image Repair Theory,” 307.

[26] Benoit, “Image Repair Theory,” 305.

[27] Frank Luntz, Words That Work: It's Not What You Say, It's What People Hear (New York: Hyperion, 2007), 3.

[28] Marie Vlachová, ed., Public Image of Security, Defence and the Military in Europe (Belgrade/Geneva: Goragraf and DCAF, 2003).

[29] Commander’s Handbook, IV-30.

[30] Baton Rouge Police Press Conference on Alton Sterling 7/6/16, accessed August 3, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=II0CTp_x5Tg.

[31] Luntz, Words That Work, 178.

[32] Luntz, Words That Work.

[33] Ronald R. Krebs, Narrative and the Making of US National Security (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 32.

[34] Luntz, Words That Work, 43.

[35] “The Army Values,” accessed August 3, 2016, https://www.army.mil/values.

[36] “National Guard of Ukraine,” accessed August 3, 2016, http://ngu.gov.ua/ua.

[37] Luntz, Words That Work, 92.

[38] Kelly P. Werder, “A Theoretical Framework for Strategic Messaging,” in The Routledge Handbook of Strategic Communication, 278.

[39] Ringsmose and Børgesen, “Shaping public attitudes,” 506.

[40] Luntz, Words That Work, 26.

[41] Luntz, Words That Work, 41.

[42] Luntz, Words That Work, 18.

[43] Luntz, Words That Work, 3.

[44] Luntz, Words That Work, 12-28.

[45] “U.S. Air Force Recruiting,” accessed August 3, 2016, https://www.airforce.com.

[46] Luntz, Words That Work, 126.

[47] Rita LePage, Mapping of StratCom practices in NATO countries (Riga, Latvia: NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2015), accessed August 3, 2016, http://www.stratcomcoe.org/mapping-stratcom-practices-nato-countries-0.

[48] LePage, “Mapping of StratCom practices.”

[49] SG(2009)0794, 3.

[50] Benoit, “Image Repair Theory,” 309.

[51] Benoit, “Image Repair Theory,” 309.

[52] David Kilcullen, “If we lose hearts and minds, we will lose the war,” The Spectator, May 20, 2009, accessed August 3, 2016, https://www.spectator.co.uk/2009/05/if-we-lose-hearts-and-minds-we-will-lose-the-war/.

- 20950 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML