Ukraine’s Security Sector Reform: Is Ukraine Taking Western Advice?

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 17, Issue 3, p.72-91 (2018)Keywords:

complexity theory, Cynefin, DCAF, defense, EU, NATO, security, security sector reform, UkraineAbstract:

The ongoing Western support to Ukraine’s security sector reform requires the assessment of the reform success. This article considers whether Ukraine’s reform is achieving effectiveness, efficiency, and democratic governance objectives. The author uses a theoretical framework of complexity theory applied to the change management research in organizational studies. The application of this framework is appealing from the perspective of complex and chaotic organizational contexts, in which the security sector can stimulate the emergence of ‘strange attractors’ for system’s adaptability. The findings suggest that Ukraine is building a shared vision following up on chaotic-framed Security Sector Reform acceleration since 2014. The gap between increased confidence in the volunteers and the army and declining confidence in general government institutions, economic burden, and Western cohesion issues constitute the risks that Ukraine’s Europeanization faces.

IIntroduction

Since Ukraine joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace program in 1994, and especially following the 2014 Euromaidan, the West has been supporting Ukraine in its security sector reform. The long time of the reform design and implementation may cause difficulties in assessing the reform’s progress. It has merit, therefore, to assess the Security Sector Reform in Ukraine in the aspects of its two key variables: governance and effectiveness.

The 2018 parade provided for a powerful show of Ukrainian military power – from rebranded Airborne Assault Troops to newly created Special Operations Forces to UAVs, new anti-aircraft missiles and the US-supplied Javelins and counterbattery radars. The parade left the impression that Ukraine military’s appearance was nowhere near the poor state of post-Soviet Ukrainian military.

The specific research questions addressed in this article are:

- How has Western assistance influenced the reform?

- Has Ukraine been following Western advice and how the West should provide optimal advice and assistance?

- How to design successful reform strategy and how to implement it?

There have been several initiatives to seek answers to these questions both from an academic and from sectoral expert and practitioner’s standpoint. A good compendium of available literature and expert efforts was developed in the joint initiative of the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) and Razumkov Center “Monitoring Ukraine’s Security Governance Challenger: Status and Needs.”[1]

This article applies the social systems theory framework to examine these research questions. A look at security sector reform as the case of the reform of the social organization allows to use insights in organizational transformation and change management developed by management sciences, including organizational theory. This approach is complementary to popular political science institutionalist framework for analyzing change as institution-building and institutional reform.

The methodology of the desk study follows the framework of complex adaptive systems theory. The security sector is viewed as a complex social system, whereas in the framework of public administration, the security sector is viewed as a large organization. Thus, Ukraine’s security sector reform was considered in this article as the case of change management.

An emerging school of organizational theory that is based on the study of complex adaptive systems is Cynefin. According to Cynefin approach to complexity in social organizations,[2] the contexts to solve the problems, including change problems in these organizations, fall into several categories.

The simple framework: This is the context of the causal, linear relationships, “the domain of best practice.” One of inherent risks of analyzing the change management problems in this framework is oversimplification of the problem issues.

Complicated context: This is the realm of ‘known unknowns,’ in which the relationships are still linear, but the presence of multiple variables makes decision mechanism more complex, than in the simple context.[3] Successful change management in this context requires the application of “good practices.”

However, most social organizations belong to complex, or even to chaotic contexts. The complex context is the domain of unpredictability and flexibility in decision making and management. Remarkably, such environments are really difficult to forecast, or analyze by customary extrapolation means, henceforth they are difficult for policy planning. In such complex organizational context, we can understand why certain things happen only in retrospect.[4] Yet, it is possible to locate the ‘instructive patterns’ in such contexts that would allow to arrive at scenario-based futures. In complex adaptive systems theory, complex relationship is related to ‘strange attractors’ that shape the dynamics of a complex system. Such strange attractors cannot be precisely discovered, but they “are random, distinct events which emerge from within the system. These can catalyze change and anchor the actions of entities around novel events providing zones of renewal and adaption which keep the system poised at the edge of chaos and thus stimulated, motivated and changing.” [5]

The scope and nature of the research was a descriptive case study supplemented with some expert interviews. The data for analysis was open source materials.

The Initial Conditions of Ukraine’s Security Sector Reform

Ukraine’s security sector reform has been ongoing since early stages of the country’s independence in 1991. As Ukraine became NATO partner state in 1994, the Military Doctrine of 1993 has eliminated the provision of Ukraine’s neutrality grounded earlier in its 1990 declaration of Independence. The strategic documents’ provisions of the time were still in their infancy as Ukraine was simply far from the Western body of policy knowledge. But practically, Ukraine was leaning Westward as demonstrated at the time by the choices of the leadership.

President Kravchuk even came up with the idea of alternative security system of Central and Eastern European states, with Poland as key partner. This idea was nullified by NATO enlargement. At the same time, Ukraine’s cooperation with NATO was a lasting one contributing to the reform of governance and management in the security sector. Kravchuk’s successor, Leonid Kuchma, pursued a “multivector” policy of balancing between Russia and the West, although he was trying to obtain security guarantees to deter Russia via the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. Ukraine’s relations with Russia were tense primarily in regard to Crimea, but that was resolved at the time by political means. Tension grew once again over the Tuzla island territorial dispute in 2003, where Ukraine also had to apply its military to deter Russia. On May 23, 2002, President Kuchma chaired a meeting of the National Security and Defense Council (NSDC), that declared as a goal of Ukraine to join NATO – a decision that was approved by presidential decree in July. Yet, Russia almost immediately pressured Kuchma to adopt “multivectoral” balancing security policy. In 2003, the Rada adopted a rather modern law “On Democratic Civilian Control of State Military Organization and Law Enforcement Bodies.”

In Ukraine’s policy expert community and in media, only “the West” was associated with the standard for security reform and not Russia, despite virtually successful military reform that Russia was able to implement. In the times of Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine was emphatically declaring its cooperation with Russia, but the latter never became the standard for reform. Instead, after 27 years of Ukraine’s independence, its elites approach security sector reform more in the framework of cooperation with the West.

Yet, the question whether Ukraine is accepting or negating Western advice is hard to answer. In fact, in the past several years, Ukrainian officials tend to assess the success, or failure, of the reform in the framework of measurable criteria. Government experts presently approach the security sector reform mainly in the framework of the NATO standards. The transition to the NATO standards would make the Defense Forces, the term that encompasses the institutions under the MoD, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA), or state security – the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) and intelligence institutions.

Many experts acknowledge the need of the civilian democratic control, which is prioritized by Ukraine’s Western partners, and is codified in the Law on Civilian Democratic Control over the Military Organization and law Enforcement Bodies.

When drafting the Law on National Security, the section on civilian democratic control drafted by presidential think tank—the National Institute for Strategic Studies—in consultations with international and local experts was placed as the top chapter. With this law and earlier Defense Bulletin, Ukraine decided to have a civilian Minister of Defense, and civilians appointed in the MOD departments.

But the problem with understanding civilian democratic control in Ukraine’s case is to excessively prioritize “civilian” over “democratic” elements. One example is the abuse of force by the police at the Maidan in early 2014. Yet, brutal use of force against the protesters was apparently authorized by democratically elected civilian president, who in Ukraine’s current model is entitled with exercising substantial control over security sector institutions. Furthermore, to a large extent “puppet” parliamentary majority voted for “draconian laws” that substantially abused the rights of protesters during the Euromaidan. Corrupt civilian officials at regional and local levels virtually defected to Russia and supported growing violence.

The Soviet roots of the Ukrainian security sector system have set some initial conditions that shape the state of the security sector today and also sets the direction. Even more, Ukraine was one of key pillars in the Soviet security and defense architecture, possessing a significant share of the former USSR’s defense forces, security forces, and the military-industrial complex.

The management essence of the Soviet and then Russian culture was in highly centralized command-like decision making, with civilian control over the “military organization” exercised by the Communist Party’s Central Committee. In parallel, informal control was exercised by power interest factions, or groups inside the Politburo and the CPSC Central Committee. The impact of the Russian imperial legacy and over 70 years of the Soviet rule left Ukraine with substantial legacy burden, which is quite hard to transform. At the time of writing this article, the term “military organization of the state” is still useed in Ukraine’s legislation, alongside the “security and defense sector” which is to be more substantialized in the bill “On National Security of Ukraine.”

The meaning of this term, deeply embedded in the Soviet thinking, as defined by Russia’s Ministry of Defense is, “the aggregate of the military and security structures of the state and its governing bodies, as well as military-political, military-scientific and other institutions involved in military affairs, activities and military personnel ensuring the interests of the country.” [6]

This school of thought in command and control, however allows for some leanness and simplicity in decision making, compared with the tedious analysis and planning process in Euro-Atlantic states’ militaries. Changing this decision making presents some professional difficulties, for example, the composition of Ukrainian units is “three-unit” based, while in NATO militaries, company has four platoons. According to a senior education and training officer, simply changing the structure to NATO standards may result initially in decreased performance of the military.[7]

In defense and security management, Ukraine has implemented some reforms in its military even before the Euromaidan. Tom Young has acknowledged Ukraine’s credit, “Any country that can deploy to a war zone (i.e., Iraq), and largely sustain a brigade-size force for three brigade rotations and recover the force … is an achievement very few other countries in the world could succeed in executing.” [8]

One of the most important government factors in Ukraine that facilitated the conflict with Russia was the weakness of the state institutions, for the most part for the reasons of corruption and nepotism. This weakness affected both the military response to the Russian aggression and it also created political instability, in which the war flourished.

A study of the Ukrainian political cohesion by Russian academic researchers, arrived at the following findings:

- Since, 1990s, the post-Soviet elite was in power in Ukraine; it used nation-building narratives to its own advantage

- The political system was a conglomerate balancing among several power groups

- Ukraine had some democratic elements, including competitive political process and a high degree of a freedom of speech and pluralism, but those did not exist within the power groups.[9]

By and large, the performance of the Ukrainian military and police forces to the Russian aggression has still to be evaluated. The decline in professional performance was very visible with the Ukrainian military. Until 2014, two governments headed consecutively by Yulia Tymoshenko [10] and Viktor Yanukovych planned to switch from conscription to professional contract service, but these initiatives failed largely because of the absence of funding for salaries, benefits, and housing. Though on paper Ukraine had a reserve system, it did not exist in reality.

An important impact on the performance of the Ukrainian military was its Soviet-style doctrine and military education, which paradoxically co-existed in selected units with Western standard training and interoperability skills acquired in partnership and out-of-area missions with NATO. This problem was augmented by substantial, times-worth relative underfunding of Ukrainian soldiers and sailors versus their Russian counterparts, which was acknowledged, but not addressed by Yanukovych’s government.[11]

At the same time, since the early 1990s, Ukraine began to establish an expert cadre and think tanks in the security and defense sector. Ukraine was the first post-Soviet country to establish a National Institute for Strategic Studies (NISS) in December 1991. In 1994, NISS became affiliated with the National Security and Defense Council, and currently it works under the President of Ukraine.[12] The experts had a “revolving door” with think tanks, thus the civic sector developed progressive technocratic expertise. Yanukovych’s presidency did not stop these experts from Western-oriented reform of the security sector, despite at times increased attention of counterintelligence. Virtually all leading experts were acknowledging in 2011-2012 that the reforms were declarative, sharply criticized the presidency and called for improvement.

The Chaos Facilitated the Change

The weakness of Ukraine’s government institutions provided justification for Vladimir Putin to call Ukraine “a complex, multi-component state formation” [13] Vladimir Socor of the Jamestown Foundation commented on the chaotic events of 2013-2014 in this regard, noting that “[t]he internal political conflict jolted the Ukrainian state from its chronic dysfunction into temporary paralysis from January through April. The Kremlin exploited that momentary opportunity to seize Crimea and parts of Donbas...” [14]

The power of the interim post-Yanukovych Ukrainian government headed by newly elected Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada Oleksandr Turchynov was extremely weak. It would be not fair to state that Ukraine provided no response whatsoever to the Russian aggression, which was the test to the effectiveness and efficiency of its military, civil security, and political leadership. Ukrainian General Staff even planned a military operation in Crimea that involved the use of the 79 Separate Airborne Brigade – the move that prompted Kremlin to hastily arrange the Crimean Verkhovna Rada’s vote on joining Russia ahead of the planned referendum.[15] But at the same time, power institutions’ inability to provide adequate response to the aggression manifested itself in three key areas: integrity, professionalism and allegiance to the state.

The integrity of the military and police staff was compromised by intertwined corruption and inadequate funding. It went alongside nepotism and medieval practice of buying the service positions. As an example, it was a commonly known practice in the years prior to the Euromaidan that junior and mid-level officers had to pay their superiors for promotion, transfer to another unit, or participation in international peacekeeping missions.

Poor ethical filters made military and police susceptible to bribery. In Crimea, Kremlin used the promises of higher salaries and housing options encouraging Ukrainian officers and contract soldiers not to resist and possibly defect to Russia.

At the initial stages, the Ukrainian military were also professionally taken aback by the use of civilians in Russian-led operations to blockade the Ukrainian troops (in multiple occasions in Crimea), or even disarm them (the case of 25th Airborne Brigade’s group in Donbas, April 2014).

Strong ties between Ukrainian security officers and Russian security agencies produced a cohort of Russia sympathizers, who shared pro-Russian interests, according to senior SBU official interviewed by the author in August 2014: such pro-Russian military officers’ mindset was one of the major problems of cohesion in Ukrainian security and the military.

Ukraine’s Deputy Prosecutor General and Military Prosecutor General Anatoli Matios said in August 2015 that some 5 000 law enforcement officers and around 3 000 military personnel were documented as having taken the enemy's side in Crimea and Donbas.[16]

In the police segment, the failure of democratic control, inadequate preparation and underfunding of the riot police was exhibited during the Maidan 2013 “revolution of dignity.” Law enforcement riot police was most likely directly responsible for the “Heavenly hundred” protesters deaths. Additionally, the police was beating up protestors, humiliating detainees, using water guns at sub-zero temperatures and other similar abuses. The riot police had inadequate technical riot management means and was importing urgently stun and smoke grenades equipment from Russia and using deadly hunting ammo. The Ministry of Interior higher officials solicited the help of low-class “titushki” helpers and paramilitary organizations, some of which had clear pro-Russian agenda, such as the Oplot group in Kharkiv. Later, many of these irregulars joined separatist units in Donbas.

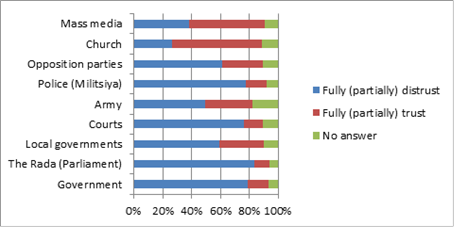

There are possibly several indicators that can measure the entire state of the system, or detect anomalies. In the human organism system such indicators are the body temperature, or the blood pressure – despite the number of complex relationships, such indicators provide certain thresholds that show if the system is performing in the allowed level. In the security sector, taking such “body temperature” is possible through a powerful indicator of measuring social trust in its institutions. The power of this indicators is such that in Ukraine’s case, it allows to compare various stages of achieved success. For example, immediately before the Euromaidan events (November-December 2013), the level of trust in the state institutions was extremely low, including in the Armed Forces, police and other elements of the political system.

Figure 1. Poll: Ukrainians had trusted only in media and church in December 2013 (Source: SOCIS and Rating Group, December 2013, http://infolight.org.ua/content/riven-doviri-naselennya-do-organiv-vladi-pidtrimka-yihnoyi-vidstavki-ta-dostrokovih-viboriv-vstu...).

Such a low level of the trust in government institutions, including the security sector institutions is often attributed to Yanukovych regime’s “predatory” character. Indeed, Yanukovych’s presidency was an outlier among successive Ukrainian administrations. Even before 2012, it exhibited very low support level in 2011. According to the data collected by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation during the Europe-wide poll in 2011, Ukrainians’ trust in the Parliament was 1.99 out of 10 points, the lowest level among 26 European states. Equally at the lowest place were the trust in the judiciary – 2.26, and the police – 2.50 points. Furthermore, the polling was conducted in 2005, 2007, 2009 and 2011 – and only in 2005, after the Orange Revolution the trust in government institutions was at the highest level of 2.4 points – still low on a 10-point scale. Compared to these values, the trust in immediate family and friends was 4.5 points.[17]

The Russian aggression was the existential threat to the society. Around 344 000 Ukrainians were mobilized, or volunteered to participate in combat in Donbas ATO since 2014.[18] Security indeed became all-society cause. Instead of supporting pro-Russian sentiment, the Russian intervention boosted Ukrainian patriotism and facilitated some systemic change. The changes in Ukraine’s national cohesion seem to be more than temporary – according to the polls by Democratic Initiatives Foundation, a record 67 percent of the public said they were proud to be Ukrainian in 2015, compared to 47 percent in 2013.[19]

In the framework of the complexity theory, the events of the Euromaidan and the “hybrid war” with Russia in Donbas present “chaotic context,” or the state of “disorder.” Remarkably, precisely such environment facilitates rapid systemic dynamics as “the domain of rapid response.” In Ukraine’s case, this response was largely provided by the civil society. As Andrew Wilson noted, “Despite inherited devastating status of the Ukrainian military, the government, in a large part pushed by civil society volunteers, was able to re-create able units within the Armed Forces, police and State Security Service, establish control over the majority of Donetsk and Luhansk provinces and eventually shed Kremlin’s plans to seize strategically important cities of Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, Odesa and Mariupol.” [20]

It this mobilizing effort, the volunteers often replaced some critical state functions. According to Kateryna Zarembo,[21] this was the evidence of the “substitution” function of civil society in weak or fragile states that is especially important as it provides the citizens with the services which otherwise would not be available. This has caused friction, as Kateryna Zarembo found in her research: “the … volunteers in fact contributed to both strengthening the state and weakening it at the same time; the outcome dependent on the context in which the volunteers took action at different times.” Zarembo believes, however, that volunteer participation failed to bring about systemic reform, but it did provide powerful democratic oversight over the state’s key defense institution.

Remarkably, some efforts of these volunteers had systemic impact beyond the defense and security sector. As Zarembo noted, volunteers in the Ministry of Defense Reforms Project Office focused on “specific” projects which could be completed within one year and fill in the most urgent gaps. The Ministry of Defense was the first ministry which not only fully adopted Prozorro, but also was the first to use it in trial mode, before its official launch and mandatory use in all public procurement tenders.

Reform’s Outlook and Risks

In 2015-2017, a large part of Western advice was focused on speeding up the coordinated reform of the security sector, with the main focus on introducing clear institutional mechanisms for civilian democratic control. One element of this advice was the assistance in drafting and the pressure upon authorities to adopt the Law on National Security. This law was initiated by the National Security and Defense Council staff. Some experts found in it a reference to the US National Security Act of 1947 as a milestone strategic document. A product of a compromise among many interest groups in security sector institutions, domestic and Western experts, the law was trying to introduce a holistic concept of the security sector, affirm and define more clearly a two-tier strategic planning system, including for example introducing the Military Security Strategy in place of the Soviet-style “Military Doctrine,” provide for deepening the reform of special services, including the need to develop new law on the Security Service of Ukraine and the parliamentary oversight committee over secret services and also to affirm civilian democratic control over the armed forces. The presidential office aligned itself with those, who urged to adopt the law, although it was not supported by some members of Presidential faction. After overcoming some resistance in the Rada and the attempt to lull through significantly amended version, the law was fully approved on 21 June 2018. By and large, security sector expert agreed that the law was a step forward, albeit it needs further improvements, especially in the areas of intelligence management and oversight and delineation of responsibilities among several institutions.

This law was fact is the latest in a series of progressively more effective strategic documents that Ukraine was developing. The Euromaidan and the forced change in 2014 brought to life several strategic documents, which are quite close to “Western-standard”: the National Security Strategy, the Concept for Security Sector Development and the Military Doctrine of 2015.

In the civil expertise sector, Razumkov Centre and DCAF conducted a series of nine conferences discussing various aspects of security sector governance reform. One important reform document was the Strategic Defense Bulletin (SDB) drafted in 2015 and turned into law in 2016. Andriy Zagorodnyuk, then-director of the Project Office of reforms, commented, “everybody understood that the reform of the Ukrainian Army needed a single plan and a single roadmap. Jointly with NATO the management of the Ministry of Defence decided to regard the SDB as the main document for building the new army. The drafting of the document was not so easy. Its uniqueness is that the SDB is the first document of such a scale, drafted by representatives of organizations who never before joined their efforts.” [22] The document had a timeframe and assessment mechanisms. The Reforms Committee of the Ministry of Defense was stipulated as key forum for decision making. Yet, some cases were successful, such as the introduction of military medicine management, or the reform of food rations, and others were not, or only starting as in the military housing reform. Alternatively, other successful projects, such as the introduction of tactical C4ISR systems “Combat Vision,” “Army SOS,” or even UAVs developed and funded by volunteer groups and private companies were on a broader scale. Likewise, RPO decided to focus on several selected projects: “Since April of this year, the Reforms Project Office will focus on the most important areas of change in the Ukrainian army: reform of the sergeant corps, food, project management, military education, procurement and combat medicine,” said the new director Petrenia. “The goal of these strategic projects is to achieve positive and irreversible changes in our army to increase our combat capabilities.” [23]

The reform of food rations was an interesting case of success on its own. After the failure to eliminate corrupt malfunctioning of outsourcing catering, PRO team headed by current PRO Director Diana Petrenia “decided to destroy it, and propose something better.” New system’s key feature was automatic order of food items from a unified catalog by the units via ProZorro online bidding system, which eliminated corruption practices and increased the quality. Military units could hire own civilian or military cooks and have strict quality control powers.[24] This was not a “linear” solution, but the creation of a new rule, coupled with empowering the units with the responsibility and “decentralizing” management.

The “irreversible changes” has a chance to become the most popular phrase in the military and beyond. Defense Minister Poltorak stated in the 2017 Armed Forces White Book, “In my estimation, this year we have reached the milestone when the transformation process of our national troops into a powerful tool for ensuring military security of the State became irreversible. We have laid a solid foundation for Ukraine’s integration into the Euro-Atlantic security environment.” [25]

In general, there is a feeling that the latest reform discussions have become less critical and consensus between the institutions and the public is emerging that the reforms were slow, the resistance is strong, and a lot remains to be done going forward. One example is the defense industry, which is lagging behind in in governance, despite several successful products, including missiles and transport aircraft that appeared on the market in 2014-2018. Defense industry “monster conglomerate” Ukroboronprom was designed as post-Soviet hybrid between a branch of the MoD and production concern. Its corporate culture is still a quasi-military institutions and it was marred in numerous corruption speculations. Yet, there seems to be a consensus between its management and civic activists. The acting CEO acknowledged that the improvement is needed to privatize its companies, which would take some time. The director of Transparency International Ukraine, Yaroslav Yurchyshyn, also pointed to the need to reform Ukroboronprom in a well-designed and implemented way: “Numerous publications about corruption at Ukroboronprom were related first and foremost to closed procurement, supplies and virtually every other activity.” [26] In the defense industry, Western partners’ recommendations have positive conditioning leverage of actual military assistance. Even though Ukraine does not receive the US and NATO member states military aid on the scale of Israel, or Egypt, it has received military assistance from 20 countries valued over $ 0.5 billion, including “night vision devices, communications equipment, mine countermeasure equipment, motor vehicles, counter battery radars, and anti-tank weapons systems.” [27] Ukraine has also a relatively high potential for development of defense technology. With government’s weak resources, potential private sector – science – civil society partnerships emerged, such as the Innovations Development Platform (www.ukrinnovate.com) to realize this potential.

In the civil security sector, the process of “Europeanization,” which some institutions, such as the State Border Guard Service went through, is continuing with the police, and to lesser extent secret services. Police bribery that was painful during the Yanukovych’s presidency has been almost eradicated today. New patrol police force works quite professionally on the streets, especially in big cities save for some mistakes explained by the lack of experience and staffing. Although experts criticize that the entire police force has virtually been re-hired with poor vetting, thus same people are working in the new police, yet some pilot projects, such as the introduction of new “detective” profession have started three years after the patrol police was established.[28] The EUAM mission is strongly assisting in the development of democratic control, integrity, but also in capacity building, such as intelligence-led policing, or forensics. Ukrainian officers conduct numerous trainings with international partners.

The most delayed is the reform of secret services. Except for the Defense Intelligence, which had some capacity-building changes as it has been heavily tasked with a warfighting function, other services continue to act as military forces, with little real democratic control and clouded in secrecy. Among those, the Security Service of Ukraine has been clouted in scandals with local and even international business in media and on expert forums. However symptomatic has been the rather uneven track record of “tug-of-war” between SSU and newly created anticorruption body NABU, in the most recent example both agencies were investigating each other over alleged corruption case against senior SSU official, SSU accusing NABU of illegal provocative investigation methods.[29] NABU is also in confrontation with the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor Office and even with the police.[30]

Remarkably, the slow pace of the governance reform, according to NATO advisor Ann-Kristin Bjergene, was the impeding factor preventing Ukraine’s integration with the EU and NATO intelligence services. Bjergene said, “Establishing efficient parliamentary control and public oversight is establishing trust! And this is the only way Ukrainian special services will become part of the Euro-Atlantic intelligence family.” [31]

The new National Security Law stipulated that the new law on SSU should be drafted by January 2019 alongside with the draft provisions to create parliamentary oversight committee over special services. A group of Rada members are working with the EUAM and NATO representation, as well as bilaterally with partners to make sure this process goes forward. The lack of progress with SSU reform has hindered the cooperation with the EUAM on capacity building training required by the service. Pursuing the intelligence reform, Ukraine established the situation room and created the “War Cabinet.” It also re-established the Joint Committee on Intelligence under the President working with the NSDC staff. Experts and government offices are working on drafting new intelligence laws.

Remarkably, Ukraine is in an institutional position quite similar to that of Georgia, where Europeanization was considered as an alternative to a pro-Russian policy. According to Chitaladze and Grigoryan, Georgian elites share a vision of moving towards NATO and the EU with a hope of “strengthening institutions and building a more democratic and functional state” thus framing “Georgia’s choice as a binary one – either the primal satisfaction of full integration into the West or succumbing to the shadowy influence of Moscow.” [32]

Europeanization in the vision of Ukraine’s ruling political elite is currently synonymous with Euro-Atlantic, i.e. NATO security orientation. This is reflected in a historically record support for membership in NATO and the EU among Ukrainians. The relative majority of 41.6 % support joining NATO, a record high for Ukraine. At the same time, 35.3 % still support Ukraine’s no-aligned status, while 16.3 % would not respond, or were undecided and 6.4 % supported military alliance with Russia and CIS member states. If the referendum to join NATO took place, 63 % would participate, with 67.2 % of those voting for the membership. Of those, 76.2 % cited the main reason for the ‘yes’ vote the security guarantees, while 31.5 % also believe that would strengthen and modernize Ukraine’s Army.[33]

NATO provides assistance to Ukraine through five trust funds and institution-building advice coordinated by the NATO Representation. Non-governmental, especially military experts understanding of “NATO standards” carries the expectations that those will raise the value of the soldier in the military and society and alter hierarchical command and control structure to raise the power of the soldiers and junior and mid-level commanders in decision making. Some visible elements were introduced in defense management, such as tactical medicine, or sniping, or uniforms. The Ukrainian military is trained by Western instructors. In Yavoriv International Training and Peacekeeping Center alone, there are about 600 instructors with the Joint Multinational Training Group Ukraine on a rotating basis. Several cases of command, control, communications, and ISR reform has been in the forces, including the Special Operations Forces and the Airborne, have been widely considered a success. Moreover, Ukraine is changing the historical legacy of the Armed Forces shifting away from the Soviet and Russian cultural and military history symbols to those representing Ukraine’s historical heritage during its fighting for independence, i.e. the army of Ukraine’s People’s Republic, or the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

One of the main risks for the successful reform is the growing gap with the trust in the governance of general political institutions. This is a characteristic of Ukraine’s governance in general and it gives a warning signal for the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections campaigns. Many experts in national security tend to characterize it as the absence of political will to conduct the reforms. This is in fact both an indicator that certain change is taking place reflected in high-level support to certain political institutions, but the general institutions, which are more an indicator of the “heath” of overall political system have little support. And this is the indicator that Ukraine’s system is facing more friction and imbalances.

Findings of the poll conducted by Razumkov Center on 1-6 June 2018 show that the most trusted institutions were volunteer organizations (65.2 %), Churches (61.6 %), the Armed Forces (57.2 %), the State Emergencies Service (51.1 %), the State Border Guard Service (50.7 %), the National Guard (48.6 %) and civic organizations (43.4 %).

The support level for law enforcement is still low, with the patrol police (35.2 %), the National Police (32.9 %), SSU (32.2 %), and NABU (17.1 %). The trust level for the President was 13.8 %, the Cabinet of Ministers 13.7 %, and the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (10.6 %). The trust to public servants was 8.6 %.[34]

Compared to these values, in a similar 2016 poll, the level of confidence was as follows: President 20.7 %, Parliament 11 %, Government 12.9 %. The Armed Forces were trusted by 57.6 %, National Police 40.7 %, and SSU by 28.4 % of the population. [35] Moreover, in December 2014, the President enjoyed 49.4 % confidence, the Cabinet of Misters 35.8 %, and the confidence in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine was 31.1 %.[36]

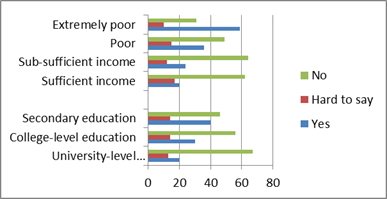

One important risk to successful security sector reform is “the cost of the security sector.” Sadly, the concept of “defense investment” is not yet in use in Ukraine. The economic cost of the Security Sector Reform confronts the “guns versus butter” question. In the past, pro-Russian sentiments were correlated to the level of income and education in Crimea and Donbas. The graph below plotted together the opinion poll indicators of Ukrainians supporting the Russian ‘mantra’ of the catastrophe of the Soviet Union disintegration and people’s income and education level divisions. The regret about the collapse of the Soviet Union was the highest among the Ukrainians with the least income level. Those with university-level education, on the contrary, overwhelmingly disapproved pro-Soviet sentiment.

Figure 2. Ukraine-wide poll: Do you regret about disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, % of total, October 2015.

(Source: Rating Group. Excluded: Crimea, http://ratinggroup.ua/en/research/ukraine/ dinamika_nostalgii_po_sssr.html)

Unprecedented for Ukraine, the heavy burden of security sector expenses – currently at 5 % of the GDP, with defense expenses over 2 %, is mitigated presently by economic recovery in Ukraine – the GDP increased 3.8 % in the second quarter of 2018. About 20 % of defense allocation is currently spent on capacity building, including delivery of new and refurbished materiel – unlike the years before the Euromaidan. Yet at the same time, the rise in real income and increasing workers emigration to the EU quickly made the soldiers’ salaries less competitive. New draft 2019 budget provides over 5 % of the GDP for security and defense expenditures, with servicemen salaries to be increased by 30 %.

Another important risk is related to lack of membership perspective in the ongoing process of Ukraine’s Europeanization. A normative dimension of the Europeanization presumes that Ukraine is changing its undeveloped, or wrong rules and procedures. This was instituted in the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement and is also the focus of the expectation of Western governments that Ukraine adopts democratic control norms and military and police rules, regulations and procedures, which will assure interoperability. But a positive dimension of Europeanization is what Thomas Risse called “we in Europe.” [37] Ukraine achieves better normative alignment with the EU; the EU should also increasingly embrace Ukraine as a value-generating member of its security community.

Thus, building the shared vision is very important in the process of change in complex adaptive systems. This also guides the political leadership. Guiding the advice and assistance toward this objective is important. In the complex contexts the CYNEFIN framework recommends, “Instead of attempting to impose the course of action, leaders must patiently allow the path forward to reveal itself.” [38] The general outlook is quite optimistic. The assessment of TI Ukraine noted that “Since 2014, Ukraine has made significant progress in monitoring and accounting for security assistance at the operational and tactical levels. Security assistance providers have imposed requirements that have encouraged recipient institutions to put in place more robust monitoring and reporting systems. Donor interviews indicate positive shifts between 2014 and 2017, with greater appreciation by Ukrainians of the need for monitoring and improvement in their systems.” [39]

At the same time, the development of a shared vision risks to be overburdened with the current political agenda at the leadership level. As Chatham House experts noted, “Building state capacity entails having a long-term vision that may need to override short-term political gain. It could be argued that because European integration requires long-term planning, there is a lack of political will to go through with it – since the political class tends to focus on short-term political and economic priorities in order to stay in power.” [40] This is all the more important, because in the systems approach, there is no room for unsustainable and not reinforced changes, which is in fact proven by Ukraine’s history to date.

Conclusion

The Euro-Atlantic security community’s member states and international institutions have been assisting Ukraine’s reforms virtually since Ukraine’s independence. Apart from institutional and internal states’ criteria, few studies were conducted to measure Ukraine’s responsiveness to Western reform advice. Even more so, the very question of whether the reform was successful is still left without an answer, on which there is consensus. The questions of the human rights abuse by the police and security forces during the Kyiv Euromaidan, as well as Ukraine’s defense and security institutions response to the Russian aggression in Spring 2014 raised questions about the effectiveness of Ukraine’s security sector. A significant contribution to the scholarship was possible through the DCAF-sponsored project Monitoring Security Governance Challenges: Status and Needs in 2014-2016 (www.ukrainesecuritysector.com), which was limited in time.

The newest Law on National Security of Ukraine refers to the security and defense sector as a coordinated system. I argued at the beginning of this article that the complex adaptive systems theory, which is gaining importance in change management studies, can provide a useful and handy framework for the analysis of Ukraine’s situation. Thus, dealing with Ukraine’s case it may be also possible to contribute to the knowledge about institutional change and statehood developed in political science. To date, the literature has focused more on the institutional framework, but I tried to shift away from linear causation approach to embrace the complexity.

The CYNEFIN method of analysis in management defines several context frameworks in organizations – from simple framework, or “the realm of best practices” to complicated contexts, where management problems are decided through choosing among alternative “good practices.” But complex contexts follow more the logic of non-linearity, self-organization and unpredictability. Turning to the metaphor of “strange attractors” in these contexts means anticipating and stimulating the change through reinforced steps. The success of the change is rooted in the leadership that allows to build a shared vision and carefully afford the system to unfold itself to progress in the new cycle.

The findings in this article suggest that Ukraine’s Security Sector Reform was accelerated with the influence of chaotic context, in which several institutional elements of the system were almost broken. I tried to present the systemic measurement indicator of people confidence in government and security sector institutions. I argued that historically, except for the immediate aftermath of the Orange revolution, this confidence was relatively low. However, since 2014, the confidence in the volunteers that played significant state capacity substitution role since the Euromaidan and the Armed Forces has reached almost 60 percent.

Yet at the same time, certain risks exist to the successful continuation of the Security Sector Reform. The economic cost of the security sector has historically been Ukraine’s vulnerability, but for the past three years, Ukraine is spending at least 5 percent of its GDP on security and defense, while the Russian aggression cost it about 20 percent of industrial capacity. This risk is mitigated by the economic recovery that seems to be steady, with Q2 2018 GDP growth of 3.8 %. Another risk is in the strategic cohesion among the EU and NATO member states in recognizing Ukraine’s European belonging.

The Ukrainian society is demonstrating historically extraordinary support to the Western institutions. If the NATO referendum were tomorrow, according to the latest poll, the ‘Yes’ vote would be 67 percent. The political elite that is currently in the government and even probably the one that would come to power as the result of 2019 presidential and parliamentary relations respects the conditionality of Western advice on reforms and is indeed a working partner. It could be argued that more Western assistance directed at the civil society and lower to middle levels of the security sector. This will broaden and enforce the reformist base, which is important to the overall system resilience.

About the Author

Maksym Bugriy is researcher in national security with the Ukrainian Institute for Public Policy and Investment Director with the Innovations Development Platform defense technology advisory. After 12-year practice as investment manager, Bugriy has been working as policy analyst since 2010. He was on the international advisory group to support Ukraine’s new National Security Law and worked with DCAF-Razumkov Centre project on Ukraine’s SSR in 2015-2017. Bugriy has MBA from Católica Lisbon School of Business & Economics and Master’s in Economics and Philosophy from Taras Shevchenko University of Kyiv.

E-mail: maksym.bugriy@gmail.com.

[1] See the initiative website, www.ukrainesecuritysector.com.

[2] David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,” Harvard Business Review, November 2007, accessed September 22, 2018, https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making.

[3] Snowden and Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making.”

[4] Snowden and Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making.”

[5] Donald L Gilstrap, “Strange Attractors and Human Interaction: Leading Complex Organizations through the Use of Metaphors,” Complicity: An International Journal of Complexity and Education 2, no. 1 (2005): 55-69.

[6] “Voyennaya organizatsiya gosudarstva,” Encyclopedia. Ministerstvo Oborony Rossiyskoy Federatsiyi, accessed June 17, 2018, http://encyclopedia.mil.ru/encyclopedia/dictionary/details.htm?id=4341@morfDictionary.

[7] Author’s interview in June 2018.

[8] Thomas-Durell Young, Anatomy of Post-Communist European Defense Institutions: The Mirage of Military Modernity (Bloomsbury Academic, June 2017), 17.

[9] “Ukrainskiy vyzov dlya Rossii,” Rabochaya Tetrad, no. 24 (RIAC, 2015), accessed September 23, 2018, http://russiancouncil.ru/common/upload/WP-Ukraine-Russia-24-rus.pdf.

[10] “BYuT planuye perebuduvaty ukrainsku armiyu,” vybory.org, September 4, 2007, accessed on September 23, 2018, http://vybory.org/articles/901.html.

[11] “Tihipko poobitsiav vyrishyty viyskovi problem,” Ekonomichna Pravda, October 6, 2012, accessed September 23, 2018, http://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2012/10/6/338555/.

[12] Oleksandr Belov, “Podobaietsia tse komus, chy ne podobaietsia, ale my budemo hovoryty te, shcho dumaiemo” (National Institute for Strategic Studies, 1999), accessed June 18, 2018, http://old.niss.gov.ua/book/belov/5.htm.

[13] President of Russia, Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club, October 24, 2014, accessed June 23, 2018, http://eng.kremlin.ru/news/23137.

[14] Vladimir Socor, “Maidan’s Ashes, Ukrainian Phoenix – A Net Assessment of the Regime Change in Ukraine Since the Start of 2014,” Eurasia Daily Monitor 11, no. 184 (17 October 2014), accessed June 23, 2018, https://jamestown.org/program/maidans-ashes-ukrainian-phoenix-a-net-assessment-of-the-regime-change-in-ukraine-since-the-start-o....

[15] “U Aksjonova s Temirgalievym Isterika (У Аксёнова с Темиргалиевым истерика: Генштаб Украины готовит освобождение Крыма от сепаратистов и российских оккупантов),” Flot 2017, June 3, 2014, accessed June 23, 2018, http://flot2017.com/posts/new/u_aksjonova_s_temirgalievym_isterika_genshtab_ukrainy_gotovit_osvobozhdenie_kryma_ot_separatistov_....

[16] “Around 8,000 Ukrainian officers sided with enemy in Crimea, Donbas, Interfax Ukraine,” Kyiv Post, August 14, 2015, accessed September 23, 2018, http://www.kyivpost.com/content/ukraine/around-8000-ukrainian-officers-sided-with-enemy-in-crimea-donbas-395725.html.

[17] “Riven doviry ukrayintsiv do vlady – odyn z najnyzhchykh u Yevropi,” The Ukrainian Week, February 11, 2013, accessed June 23, 2018, http://tyzhden.ua/News/72023.

[18] “Poroshenko: 344,000 people become combatants in eastern Ukraine,” Ukrinform, August 22, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-polytics/2522485-poroshenko-344000-people-become-combatants-in-eastern-ukraine.html.

[19] Kateryna Shapoval, “Socioloh Iryna Bekeshkina za dopomohoyu vlasnykh doslidzhen preparuie krayinu (Соціолог Ірина Бекешкіна за допомогою власних досліджень препарує країну),” Novoya Vremya, Democratic Initiatives Foundation, April 18, 2016, https://dif.org.ua/article/sotsiolog-irina-bekeshkina-za-dopomogoyu-vlasnikh-doslidzhen-preparue-krainu.

[20] Andrew Wilson, “Five Things the West Can Learn from the Ukraine Crisis,” Quartz, October 8, 2014, accessed September 23, 2018, http://qz.com/277502/five-things-the-west-can-learn-from-the-ukraine-crisis/.

[21] Kateryna Zarembo, “Substituting for the State: The Role of Volunteers in Defense Reform in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine,” Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal, no. 3 (2017): 47–70, https://doi.org/10.18523/kmlpj119985.2017-3.47-70.

[22] Andriy Zagorodnyuk, “The Turning Point for Ukrainian Military Reform: What Is the Strategic Defence Bulletin and Why Is It So Important?” Ukrayinska Pravda, July 11, 2016, accessed June 23, 2018, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/columns/2016/07/11/7114416/.

[23] “Diana Petrenia Becomes New Head of MOD Reforms Project Office,” The Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, Reforms Project Office, June 25, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018, https://defense-reforms.in.ua/en/news/kerivnik-xarchovoi-reformi-u-zsu-diana-petrenya-ocholila-proektnij-ofis-reform-mou.

[24] Illia Ponomarenko, “Reform Brings New, Better Taste to Army Rations,” Kyiv Post, August 3, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018, https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/reform-brings-new-better-taste-to-army-rations.html.

[25] “White Book 2017, The Armed Forces of Ukraine,” Ministry of Defense of Ukraine (2018), accessed September 23, 2018, http://www.mil.gov.ua/content/files/whitebook/WB-2017_eng_Final_WEB.pdf.

[26] “Chto ozhydaet ukrainskij VPK – mnenija ekspertov (Что ожидает украинский ВПК – мнения экспертов),” NV BIZ, accessed September 23, 2018, https://biz.nv.ua/publications/chto-ozhidaet-ukrainskij-vpk-mnenija-ekspertov-2458284.html.

[27] “Ukraine and the World,” Defence Express, September 19, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018, https://defence-ua.com/index.php/en/publications/defense-express-publications/5379-ukraine-and-the-world.

[28] “Policiyi slid perejty vid tochkovyx zmin do instytucijnyx reform, – zvit ekspertiv (Поліції слід перейти від точкових змін до інституційних реформ, – звіт експертів),” UMDPL Association, June 27, 2018, accessed September 22, 2018, http://umdpl.info/police-experts.info/tags/reforma-politsiji/.

[29] “SBU protiv NABU: Sytnika predosteregli ot unichtojeniya dokumentov (СБУ против НАБУ: Сытника предостерегли от уничтожения документов),” Liga News, September 13, 2018, accessed September 22, 2018, http://news.liga.net/politics/news/sbu-protiv-nabu-sytnika-predosteregli-ot-unichtojeniya-dokumentov.

[30] “Sytnik ne smoh predstavit deputatam otchet o dejatelnosti NABU (Сытник не смог представить депутатам отчет о деятельности НАБУ),” Novoe Vremia, September 19, 2018, accessed September 22, 2018, https://nv.ua/ukraine/events/sytnik-ne-smoh-predstavit-deputatam-otchet-o-dejatelnosti-nabu-2495201.html.

[31] Ann-Kristin Bjergene, “General Challenges of Intelligence Service Reform,” in Proceedings from the Third International Conference “Governance and Reform of State Security Services: Best Practices,” 24 May 2016, Kyiv, Ukraine, Project “Monitoring Ukraine’s Security Governance Challenges” (DCAF/Razumkov Centre, 2017), 41-45, accessed September 23, 2018, https://ukrainesecuritysector.com/publication/conference-proceedings-3-governance-reform-state-security-services/.

[32] Anna Chitaladze and Tatevik Grigoryan, “Understanding Europeanization in Georgia and Armenia – Discourses, Perceptions and the Impact on Bilateral Relations,” Analytical Bulletin 8 (2015), 29-54, accessed September 23, 2018, https://cccsysu.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Chitaladze-Ana-Grigoryan-Tatevik-2.pdf.

[33] Kyiv International Institute for Sociology Nation-wide poll, Interfax Ukraine, Yevropeyska Pravda, September 11, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018, https://www.eurointegration.com.ua/news/2018/09/11/7086755/.

[34] Razumkov Centre, June 2018, accessed September 23, 2018, http://razumkov.org.ua/uploads/socio/2018_06_press_release_ua.pdf.

[35] “Citizens of Ukraine on Security: Personal, National, and its Elements. Results of a nationwide sociological survey conducted by the Razumkov Centre, Kyiv 2016” (DCAF-Geneva, Razumkov Centre, 2017), accessed September 23, 2018, https://ukrainesecuritysector.com/publication/citizens-ukraine-security-personal-national-elements-survey-2-2017/.

[36] “Reytyng Presydenta katastrofichno padaye,” Esspresso TV, May 31, 2017, accessed September 23, 2018, http://expres.ua/news/2017/05/31/245122-reytyng-prezydenta-katastrofichno-padaye.

[37] Thomas Risse, “European Institutions and Identity Change: What Have We Learned?” July 30, 2003, accessed September 23, 2018, http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/atasp/texte/030730_europeaninstandidentity_rev.pdf.

[38] David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,” Harvard Business Review, November 2007, accessed September 22, 2018, https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making.

[39] Making the System Work. Enhancing Security Assistance for Ukraine (Transparency International Defence and Security and Transparency International Ukraine, 2017), accessed September 23, 2018, http://ti-defence.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Making-the-system-work-TI-Defence-Security.pdf.

[40] Kataryna Wolczuk and Darius Žeruolis, “Rebuilding Ukraine: An Assessment of EU Assistance,” Chatham House Research Paper, August 16, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018, www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-08-16-rebuilding-ukraine-eu-assistance-wolczuk-zeruolis.pdf.

- 36077 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML