Presenting a Strategic Model to Understand Spillover Effects of ISIS Terrorism

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 16, Issue 2, p.41-57 (2017)Keywords:

foreign fighters, ISIS, regional security, spillover effects, TerrorismAbstract:

Understanding the nature and the extent of the future threat from ISIS has been a key question for scholars, policy makers and security professionals since ISIS started losing significant grounds in Syria and Iraq. This article analyses ISIS terrorism and its possible spillover effects from a regional security perspective by presenting a strategic model to develop options for the policy makers. A strategic understanding, supported by a model that has been designed to capture all possible variables and their interaction which each other, is necessary to understand the future direction of the threat. Many scholars agree that the threat is not only about the organizational structure of ISIS but also its ideological aspect, therefore the model presented here connects the facts and the ideology with variables at three different levels: regional political level; ISIS and its organizational structure; and individual level variables. The model was designed to capture changes with relevant data thus providing a strategic data-driven understanding of the threat.

Regional political developments and how ISIS reacts to those developments are the main concerns at the first two levels of analysis. Foreign fighters and other sympathizers are the most important subjects of the study at the individual level with the assumption that the future threat will diffuse through foreign fighters and self-radicalized lone actors.

Introduction

ISIS poses a significant threat to both Middle East and global security. Studies analyzing the organizational structure, recruitment process, target selection and attacks of ISIS by focusing its leaders and followers’ public and social media discourses found that the organization developed a decentralized attack strategy by encouraging its sympathizers for the attacks and not addressing direct attack plots.[1] Attacks carried out by ISIS affiliated militants in 2015, 2016 and 2017 indicate that the organization is becoming a more global threat. Although recently ISIS lost significant grounds both in Syria and Iraq, its last stronghold places to be expected to fall soon, there is also convincing evidence that ISIS adapts to these changes.[2] The loss of territory was followed by loss of manpower as many foreign fighters escaped from Syria and started to return to their home countries or to a third country, continuing however to keep their contacts with the organization.[3]

Mostly operating in Syria and Iraq and establishing a governance structure in Syria, ISIS received a significant number of foreign fighters in the past. ISIS not only created a regional insecurity and instability but also spread the terror to a global level through foreign fighters and other radical individuals called “lone actors.” Returning foreign fighters are already involved in terrorist attacks, particularly in Europe, and current indications demonstrate that returnees and lone actors will continue to pose significant threat to the global security.

This article analyzes ISIS terrorism and its possible spillover effects from a regional security perspective and attempts to present a model for developing alternative directions for the policy makers. In order to make an accurate analysis, it argues that three types of data should be collected and cross-analyzed to measure the causal relationship at different levels. The model created to understand the spillover effect of ISIS terrorism starts with the regional level events (regional level analysis) and continues with the policy outcomes of regional actors. At the second step, an organizational level approach focusing on ISIS (as a non-state actor) attempts to develop an understanding of the organization. Lastly, the study argues that individual level data collection focusing directly on key individuals and known foreign fighters as well as individuals at risk will be necessary to predict the nature and the extent of the spillover effect of ISIS terrorism.

Security at the Global Level in 2016 and 2017

ISIS carried out or claimed responsibility of more than 140 terrorist attacks in 30 countries other than Iraq and Syria since declaring its self-proclaimed Islamic State (the caliphate), i.e. from June 2014 until the first two months of 2017.[4] According to the Esri Story Map project data, until September 4, 2017 133 attacks were carried out at the global level killing more than 800 people (excluding Iraq and Syria).[5] Those attacks taking place from North America to Australia and Europe to South Asia clearly show that since 2014 ISIS became a more global threat than a regional one (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). Although most of the attacks (including the ones with most causalities) were carried out in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the return of foreign fighters increases the concerns for the global security in the Western world. Recent attacks in 2016 and 2017 require experts and policy makers to develop a better understanding of the spillover effect of ISIS terrorism at the global level.

Available data regarding the terrorist attacks and public perception of safety and security presents an interesting paradox. According to the 2017 Global Peace Index Report, MENA region ranks the least peaceful region in the world for the fifth successive year and Europe remains the most peaceful region in the world, with eight of the ten most peaceful countries coming from this region.[6] On the other hand, Special Eurobarometer Survey on Europeans’ Attitudes toward Security indicates that, although Europe remains the most peaceful region in the world, most of the Europeans rank terrorism as the most important threat (49 %) to the security of EU citizens and their feeling of secu-

Source: CNN International, “Mapping ISIS attacks around the World” (Sanchez et al, 2016).

Figure 1: ISIS Attacks at the Global Level 2016.

rity deteriorating.[7] Respondents to the survey believe that many of the security threats the world faces are becoming more severe; two-thirds of respondents (68 %) think that the challenge of terrorism is likely to increase over the next three years (up from 51 % in 2011), whereas only 10 % believe it is likely to decrease. Security data showing that a region is safe does not mean that the public fully enjoys the level of security demonstrated in the data. Public perception of the security and fear of victimization as well as increasing concerns for the possibility of attacks determines the actual demand for more effective security policies. In other words, in Europe, there is a demand not only to be safe but also—and may be, more importantly—to feel safe.

The attacks in Paris in November 2015 have been marked as the worst violence (130 killed and 368 wounded) in France since WWII and “the most sophisticated assault in the West.” [8] After the attacks many experts and commentators claimed that the world entered a new area of counter terrorism and the Paris attack became a game changer for the West as well as at the regional and transnational security domain. The San Bernardino attack in the US in December 2015 that resulted in 14 dead and 24 injured increased the attention to the capacity of ISIS to conduct remote attacks even without sending direct orders for an attack plot. In 2016, ISIS claimed responsibility for 16 deadly attacks in the West (in the US, France, Belgium, Turkey, Germany) killing 302 and wounding 1277. Until September 2017 ISIS carried out (or inspired) six major attacks (in the UK, France, Turkey, and Spain) and killed 91 and wounded 327.[9] According to latest Europol report, majority of attacks claimed by ISIS in Europe are masterminded and perpetrated by individuals inspired by ISIS and the organizational structure of ISIS played no or very limited direct role in planning and executing the attacks.[10] According to the same report, the number of arrests for jihadi terrorists activities has increased dramatically in the EU during the last few years with more than 600 arrests in 2015 (395 in 2014, 687 in 2015) and also the number of plots by jihadi terrorists have never been as high as in the period 2014-2016. Europol concludes that there is an IS-effect on jihadi terrorism in Europe from the turn on 2013.

Available data on ISIS attacks at the global level indicates that inspired attacks by people who have previously travelled to Syria and trained by ISIS pose a significant risk for States receiving those individuals. A recent report by Swedish Defense University points out a risk that “some of the returning foreign fighters intend or can be swayed to commit attacks in Sweden and other countries outside of the conflict area, and at least two Swedish returnees were involved in the recent Paris and Brussels attacks.” [11]

Investigations of some of the attacks between 2015 and 2017 revealed that some of the attackers had traveled to Syria and trained by ISIS before the attacks. In July 2015, a 20-year-old suicide bomber with links to ISIS killed more than 30 people at the Cultural Center in Suruc, Southeast part of Turkey and very close to the border with Syria.[12] Investigations after the November 2015 Paris attacks (130 death and 368 wounded) also found individuals who were returnees from Syria to be involved in the attack.[13] On January 12, 2016 a suicide bomber killed 10 people and wounded 15 at Sultanahmet square, a popular tourist district in Istanbul. The attacker, Nabil Fadli, a Syrian born in 1988, was later identified as a registered Syrian refugee, affiliated with ISIS before his travel to Turkey.[14] On March 22, 2016 three coordinated attacks killed 35 and wounded 340 people in Brussels and at least two of the suspects had previously travelled to Syria and fought for ISIS.[15] Further analysis of similar cases shows that individuals who have been recruited by ISIS and traveled to Syria started to engage in terrorist acts in close cooperation with individuals who never traveled but were radicalized in their home countries. Therefore, there are significant indications that returnees started to be the agents of spillover between 2015 and 2017. Some of the attacks however carried out by lone actors and self-radicalized individuals, therefore these two phenomena (interaction of returnees and lone actors) needs to be carefully examined in order to reach reliable conclusions as to the future direction of the threat.

Security and related issues are also listed amongst the most discussed topics in 2015. Facebook analyzed and revealed its data on conversations at the global level and found that November 13 Paris attacks took the second place after US presidential election.[16] Other related topics such as “Syrian civil war and refugee crises” took the third place, “fight against ISIS” became the seventh, and “Charlie Hebdo attack” listed eighth most talked-about topics at the global level in 2015. When you compare the same data with 2014, only “conflict in Gaza,” as a security related topic, appeared in the list as the sixth talked about topic (Table 1). Interestingly, in 2016 none of these issues were in the Facebook’s top ten most talked global topics.[17] However, a recent Pew Research Center data shows that ISIS is still considered as the top threat at the

Source: Esri Story Map 2017 Terrorist Attacks.

Figure 2: ISIS Attacks at the Global Level 2017.

global level.[18] These two data sources and the Eurobarometer survey mentioned earlier illustrate that although people stop talking about the security related issues overtime, how they conceive threat and their threat perceptions do not change significantly. Security related issues and concerns became a significant part of our daily lives, an important determinant of our personal and professional choices, have a direct impact on our social and political behaviors. Therefore, addressing the complex security problem of the day requires a multi-dimensional and more complex methodological analysis. Descriptive findings are mostly irrelevant to the development of comprehensive policy solutions based of understanding of the future direction of the threat. By providing a framework and a model this study intends to create a scientific analysis tool to measure possible spillover of ISIS terrorism.

Security concerns and related issues have been related to several major issues in the Middle East such as the Israel-Arab conflict, developments followed

Table 1. Top Global Topics in 2014, 2015 and 2016.

| Top Global Topics of 2014 | Top Global Topics of 2015 | Top Global Topics of 2016 |

1. | World Cup | US Presidential Election | US Presidential Election |

2. | Ebola virus outbreak | November 13 Attacks in Paris | Brazilian Politics |

3. | Elections in Brazil | Syrian Civil War & Refugee Crisis | Pokemon Go |

4. | Robin Williams | Nepal Earthquakes | Black Lives Matter |

5. | Ice Bucket Challenge | Greek Debt Crisis | Rodrigo Duterte & Philippine Presidential Election |

6. | Conflict in Gaza | Marriage Equality | Olympics |

7. | Malaysia Airlines | Fight Against ISIS | Brexit |

8. | Super Bowl | Charlie Hebdo Attack | Super Bowl |

9. | Michael Brown/Ferguson | Baltimore Protests | David Bowie |

10. | Sochi Winter Olympics | Charleston Shooting & Flag Debate | Muhammad Ali |

Source: Data from Facebook Newsroom: 2014, 2015 and 2016 Year in Review.

by the Arab Spring, Syrian civil war, etc. All those issues have deep historical and political backgrounds and almost turned into frozen policy areas, which produce no long-term solutions. Most of these conflicts and issues are also blamed for being the root causes of recently emerging security threats and the birth of ISIS itself. ISIS emerged in 2006 from the remnants of Al-Qaeda in Iraq after the American invasion; the group became internationally known after expending to Syria in 2013 and declaring global Caliphate (Global Islamic State) in 2014.[19] As ISIS becomes weaker in Syria and Iraq, there are indications that the ideology and frozen policy issues that radical groups rely on for their existence will remain in the future. Therefore it is likely that the threat will appear with a new face; hence, the international security community needs to focus on the re-emergence of the threat with different structure, new actors and diverse modus operandi by considering all relevant aspects in a single comprehensive model. This study is an attempt to create an effective tool to examine multiple aspects of the issue with account of their interaction.

ISIS and Security in the Middle East: Introduction to the Spillover Model

Despite other frozen policy issues in the Middle East, security politics progress over the years and most of the changes are related to global, regional and domestic developments. Not all changes produce positive results all the time but as the countries reach an agreement on regional problems and develop a working cooperation environment, promising results obtained in countering threats and further achievements become more likely. In addition to the development of a common response to the ISIS threat, a multi-disciplinary approach should also be developed and regional policies have to be analyzed with account of the interplay of all possible causes and effects, since policy outcomes and negative externalities (such as terrorist attacks) do happen in connection with internal and external factors.

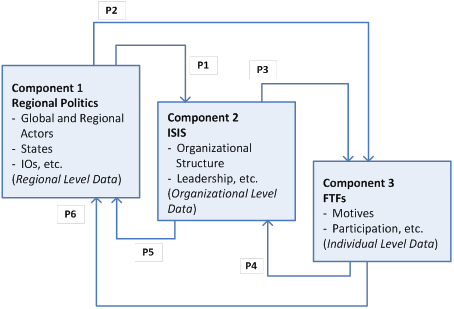

Cascade Path Model to Measure Spillover

Understanding the spillover effect of ISIS terrorism requires creating a model to capture all changes (both internal and external) at three different levels to understand the direct or indirect causal relationships amongst various variables. The model presented in Figure 3 shows a cascade model (assuming each component has an independent impact on each other) and six paths showing the possible interaction between three different levels. These levels were identified on the basis of a theoretical understanding of the spillover model, in which regional politics and ISIS, a non-state actor, interact with each other (that interaction produces negative externalities) whereas foreign fighters are presented as the agents of the spillover in the same model.[20]

According to the model, all these levels have direct and indirect impacts on regional security. The model will help us break down the complex issue where focusing on each path will contribute to understanding the power of each interaction and, hence, developing new policy alternatives. This model is also intended to be used as a framework for developing a data collection instrument to create a database for further analysis.

Component 1: The first component of the model focuses on regional politics and proposes the collection of regional level data and it involves following major events and policy changes of regional actors. Path 1 (P1) refers to one-way causal relationship between regional politics and ISIS; it shows how regional politics will affect the ISIS (its policies, organizational structure, leadership etc.).

Figure 3: ISIS Attacks at the Global Level 2017.

P2 refers to how regional politics might have a direct impact on individual level data such as foreign terrorist fighter (FTF) recruitment, constructing new individual level narratives, etc.

Component 2: As the first component of the model focuses more on regional and state level analysis, the second component focuses on institutional level analysis and is intended to analyze ISIS from an organizational point of view. Changes in the organizational structure, developing new or adaptation of existing discourses and ways of countering actions undertaken by international coalition or individual states’ policies are all examined at this level. In this component, it is also intended to follow ISIS from an analytic perspective and identify changes in the organizational structure, method of governance and management style based on P1 and P4. This component also has two outgoing paths and P3 refers to the effect of ISIS on FTFs and P5 – on how ISIS creates an impact on regional policies.

Component 3: In the last component, the model seeks to collect data at the individual level. It includes variables to identify the patterns and characteristics of FTFs at the global level. In this component, the intention is to collect data from open sources about the individuals who are prone to or have already joined ISIS and to try to understand the dynamics of involving the organization and power of narratives. In the path structure of the model, P4 stands for the possible effects of individuals on the organization and P6 refers to FTFs’ possible effects on changing regional politics or a specific policy.

Applying the Model to 2015 and 2016

Changes in world politics do not happen overnight. Although some single events create enormous impacts in a shorter time period, in most cases significant change comes upon certain preconditions or as a result of the influence of direct/indirect causes. Regional political and policy level changes play an important role to understand the security structure of a region. From the perspective of the model created in this study, these changes have a significant impact on the lower levels (to ISIS and FFs). In other words, regional changes will have an impact both on the variables related to ISIS as an organization and to the FFs.

Scholars focusing on regional studies and in particular on the Middle East mostly agree with the argument that the region is suffering from the lack of regional integration and linkages necessary to enter the global world.[21] Theories of international and comparative politics provide many explanations why the region does not have a stable regional system and why states in the region cannot develop regimes that contribute to peace and an inclusive economic prosperity.

Comparing the Middle East with other regions also provides an explanation why the Middle East could not establish a stable regional system. Etel Solingen, after conducting a comparative analysis between East Asia and the Middle East, claims that those two regions developed a divergent development path over the last century despite their initially shared conditions.[22] She concludes that competing models of political survival explain the difference in economic, political and regional developmental difference, while “East Asian leaders pivoted their political control on economic performance and integration in the global economy whereas Middle East leaders relied on inward-looking self-sufficiency, state and military entrepreneurship and a related brand of nationalism.”

The Middle East as a regional entity does not have much power and influence hence almost zero ability for establishing a security policy to mobilize regional states. The lack of a powerful regional institutional structure and limited abilities of regional states to create a well-functioning security structure leaves a wide area for global actors to interfere and define regional policies. Therefore, the Middle East remains referring only to a geographical entity rather than a political, economic, cultural or a military structure. Hence, it would be a fair argument to claim that there is no structure in the region to bring peace and stability. Main actors in the regional politics are states (both internal and external but external states have more influence), international organizations (both regional and global institutions, with the later having more power) and non-state actors (global level NGOs mostly providing positive impact and terrorist organizations having negative impact on the regional security.)

According to Curtis R. Ryan, regime security is the key driver of alliance politics in the Middle East and succinctly explains the international relations of the region.[23] That is, Arab states are concerned over their regimes as political developments emerge in the region. Ryan claims that “Arab regimes remain frequently trapped in an internal and external security dilemma of their own making and obsessed with ensuring the security of their ruling regimes against both internal and external challenges. In sum, we can argue that the Middle East international relations are shaped and defined by an interplay between domestic and regional influences.” [24]

In 2015 and 2016, the MENA did not progress; not even a single step was made towards constructive institutional cooperation. As presented earlier in this study, security problems in the region became more global and earlier complications became more complex. 2015 started with an ongoing war between Kurdish forces of People’s Protection Units (YPG) and ISIS militants in Northern Syria over Kobani (Syrian city close to Turkish border.) After 113 days of war between the two groups, YPG won the battle and re-captured the city from ISIS on January 27, 2015. Within Syria, the pattern of fighting from the previous years continued, sectarian and ethnic differences started to drive clashes, and power has shifted from large standing armies to local militias in 2015.[25]

Among others, one significant event of 2015 was the changed Russian approach to the Syrian problem. More specifically, during the UN General Assembly meeting on September 28, Russia clearly showed a significant shift followed by Russian airstrikes on ISIS targets in Syria on October 1, 2015. New developments in 2015 clearly showed that Russia as an active actor and participant in the regional politics changes the way the Syrian crises is and can be handled. However, that shift neither significantly contributed to the security of the region nor made any changes in the power structure. ISIS also continued to hold on to most of its territory, or even expand it, established a government bureaucracy, and recruited new fighters from all over the world.

Measuring the effect of regional developments on the organizational side of ISIS is the key objective of the first component of the model. Available data suggests that regional developments had limited impact on diminishing the power of ISIS at the global level. Both in 2016 and 2017 Western coalition forces, with significant involvement of local opposition and militia groups, advanced to gain territories previously claimed by ISIS in Syria and Iraq, however this battle is not over yet. Military experts expect to claim a full-scale victory by retaking Raqqa (the so called capital of the Islamic State) before the end of 2017. Despite this military defeat, in 2016 ISIS either directly organized or claimed responsibility of many deadly attacks carried out by returnees or self-radicalized individuals. As Daniel Byman, senior fellow at Brookings Institution, puts it, in 2016 and 2017 ISIS showed its ability to conduct attacks at the global level other than the conflict area.[26] What to expect after a military victory in Syria and how to deal with the potential of ISIS to conduct attacks at the global level has been and will be a major issue for the following months and the ideology will be the major tool for the organizational structure to recruit members for potential attacks.[27]

The structure and the ideology of ISIS developed within the context of the Iraqi insurgency of the early 2000s. It began as a branch of Al-Qaeda, founded in Iraq in 2004 after the American invasion and headed by Ayman al-Zawahiri and mostly shaped by Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi until he was killed by U.S. airstrikes in Iraq.[28] In October 2006, Abu ‘Umar al-Baghdadi has been named as the leader of the group by the Mucahidin Shura Council in Iraq. Between 2006 and 2013, the group named itself as the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) and mostly considered as Al-Qaeda in Iraq by the Western media. In April 2013, Abu ‘Umar al-Baghdadi announced the Islamic State’s expansion to Sham, the Arabic word for greater Syria. On June 2014, ISIS declared itself the caliphate and Baghdadi announced himself as the caliph of all Muslims throughout the world.

At every stage of its development, ISIS constructed a governance structure including management of educational, judicial, security, humanitarian and infrastructure systems. Caris and Reynolds, based on the available data and evidence, explain in detail how ISIS has demonstrated the capacity to govern both rural and urban areas in Syria under its control.[29] With its weaknesses and strengths, ISIS developed administrative capacities in Syria, and in order to understand the operation strategies of the organization that structure should be carefully examined. Available data do not support the suggestion that the organizational structure of ISIS changed in 2015 and there is not much evidence to measure how military advancements in 2016 changed the organizational structure of ISIS.

Addressing the return of foreign fighters became a high priority for Western countries and recently foreign fighters have been the subjects of important debates. Although the term foreign fighters had been used for a long time, recently it has been mostly used in reference to people who travelled to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS and other terrorist organizations. Many conflicts in the world received people who have volunteered to fight for their cause, and we can find examples of this in Afghanistan during Russian invasion, in Balkan conflict and as well as in the more recent Ukraine-Russia conflict over Crimea. This phenomenon is not specific to a group of people, to a religion or a nation. However, the scale of the threat is immense due to direct influences of technological advances as well as the outbreak of civil war and sectarian violence in several countries in the Middle East.

The Soufan Group released a report in June 2014 presenting the known numbers and other available background information on Foreign Fighters in Syria identifying approximately 12,000 foreign fighters from 81 countries.[30] In a later report, released in December 2015, it is indicated that “despite the sustained international effort to contain the Islamic State and stem the flow of militants traveling to Syria, the number of foreign fighters have more than doubled.” [31] The same report also presents that “between 27,000 and 31,000 people from at least 86 countries have traveled to Syria and Iraq to join the Islamic State and other violent extremist groups, and efforts to contain the flow of foreign recruits to extremist groups in Syria and Iraq have had limited impact. The most worrisome fact for the European countries is that “the number of foreign fighters from Western Europe has more than doubled since June 2014, and the average rate of returnees to Western countries is now at around 20-30 %, presenting a significant challenge to security and law enforcement agencies that must assess the threat they pose.” In 2015, a significant number of foreign fighters continued to join ISIS and some of them returned back to their home countries. Not all of them engaged in a terrorist activity but the risk for home countries is very high.

Analysis and Conclusion

In order to understand the spillover effect of ISIS terrorism three components—regional politics, ISIS, and foreign fighters—were presented and assumed to have an independent impact on each other in this paper. Therefore, the model consisted of direct relationship amongst all these components. Available data supported some of the theorized connections but for more comprehensive results longer term data collection and its analysis is required and that is beyond the limits of this study. Since the main purpose of this study is to present the model and suggest an ongoing data collection activity to create a database for an extensive analysis, it suffices to make some general conclusion with the available data.

Our model indicates that regional political developments in the Middle East do not promise a comprehensive institutionalized cooperation environment. In addition, regional political developments and changes in policies in 2015 did not cause significant damage to ISIS, nonetheless Western coalition forces made significant progress to defeat ISIS in Iraq and Syria by re-taking the claimed territory. Meservey reported that ISIS lost 14 % of its claimed territory in 2015, but how that effected the organization and its power structure is unclear.[32] The long-term impact of current military success is not clear yet and requires further political and social successes both at the regional and global level. Whether or not regional actors’ specific policies create any type of impact on the organization requires the collection of more data. Path 1 (P1) in our model presented earlier in Figure 3 shows no significant impact on ISIS to reduce its power in 2015.

In 2015, regional key actors could not develop an advanced cooperation to reduce participation to ISIS. However, increase in the level of intelligence sharing and more cooperation at the technical level produced promising results in comparison to previous years. If regional political shift can put ISIS in a difficult position that it cannot survive, it would also lose control over the members and foreign fighters would seek opportunities to flee from Syria or Iraq. However, until 2015, there was no indication of such development which happened later in 2016 and 2017. Therefore, P2 in our model indicated limited but still promising outcomes in 2016 and 2017.

In order to measure the impact of ISIS on FTFs (P3), the measurement should include variables about individuals who already joined the group and characteristics of potential FTFs abroad. Statements of people who managed to escape from ISIS indicate that the organization is not as they were expecting to be.[33] More data is required to make a clear assessment regarding ISIS and FTFs interaction. Until 2016 and also in 2017, available data indicates that ISIS created a strong organization structure using social media effectively and also managing all recruits effectively as they join their forces.

Key players in the regional politics established a coalition to counter ISIS’s territorial expansion, but the real impact on the organization is not sufficiently clear to reach a conclusion of a final defeat of ISIS. ISIS still holds the advantage of using global sympathizers and former fighters who returned to their home countries as the agents of spillover. Regional politics cannot be successful unless all components of the problem are addressed and the interaction amongst them is assessed cautiously. Scholars should go beyond the descriptive studies and produce more policy options for decision makers by mostly addressing the individual level push and pull factors to reduce ISIS’s advantage to recruit more people to be employed in future attacks. Military and law enforcement solutions will be effective only if States and international organizations increase their tactical level cooperation and extend this cooperation to a more strategic level by understanding each individual component and the interaction among components thoroughly. The strategic model presented in this study will provide analytical information that will help policy makers to identify the issues requiring more attention and also will produce information to address possible vulnerabilities emerging after new political or social developments.

After defeating ISIS in Syria and Iraq, a new era of fight will start that will include greater focus on ideology, methods used to recruit new members, and efforts to reduce the likelihood of individuals conducting lone actor attacks. A short term tactical solution will include more international cooperation and sharing data on the returnees and possible radicalized individuals as well as members of the group. Another more strategic level approach requires close understanding of the background factors triggering radicalization of individuals and how national and international political developments feed this circle. Each component will only be valuable if the interaction of global, national and individual factors leading to violent attacks could be better understood. A more effective strategy to defeat ISIS and to reduce capacity to attack at the global level depends on a multi-disciplinary understanding of the spillover and developing multi-sectoral policy responses to the future threat of ISIS.

About the author

Dr. Cüneyt Gürer is Associate Professor of Security Studies. He is an Adjunct Faculty Member of George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. His research interest are global and regional security policies, methodological approaches to security and policy diffusion. He earned his PhD from Kent State University Department of Political Science in 2007.

[1] Thomas Hegghammer and Petter Nesser, “Assessing the Islamic State’s Commitment to Attacking the West,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 4 (August 2015): 14–30; Jytte Klausen, “Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38, no. 1 (December 2014): 1–22.

[2] “Syria: ISIS to be driven out of Raqqa within two months, claims top commander,” Independent, August 28, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-driven-out-of-raqqa-syria-two-months-ypg-nowruz-ahmed-a7917326.html (accessed September 6, 2017).

[3] “ISIS faces exodus of foreign fighters as its ‘caliphate’ crumbles,” The Guardian, April 26, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/26/isis-exodus-foreign-fighters-caliphate-crumbles (accessed September 6, 2017).

[4] For the global level data and other information on attacks see Ray Sanchez, Tim Lister, Mark Bixler, Sean O’Key, Michael Hogenmiller, and Mohammed Tawfeeq, “ISIS goes global: 143 attacks in 29 countries have killed about 2,043 people,” CNN International Edition, January 21, 2016, http://edition.cnn.com/2015/12/17/world/mapping-isis-attacks-around-the-world (accessed September 7, 2017).

[5] “Esri Story Map 2017 Terrorist Attacks,” https://storymaps.esri.com/stories/terrorist-attacks/?year=2017 (accessed September 7, 2017). The data derived from the web site and calculated manually by the author to exclude cases from Syria and Iraq.

[6] Institute for Economics and Peace, “Global Peace Index 2017 Measuring Peace in a Complex World,” http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2017/06/GPI17-Report.pdf (accessed September 7, 2017).

[7] European Commission Public Opinion, “Special Eurobarometer 432, Europeans’ Attitudes Towards Security,” http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/search/security/surveyKy/2085 (accessed September 7, 2017).

[8] Emily Estelle and Harleen Gambhir with Kaitlynn Menoche, “Network Graph of ISIS’s Claimed Attack in Paris” (Institute for the Study of the War, 15 November 2015), http://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/network-graph-isiss-claimed-attack-paris (accessed September 7, 2017).

[9] “Esri Story Map 2017 Terrorist Attacks.” The data derived from the website and calculated manually by the author.

[10] “Changes in Modus Operandi of Islamic State (IS) revisited,” European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (Europol, 2017), https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/2017-eu-terrorism-report-142-failed-foiled-and-completed-attacks-1002-arrests-and-14... (accessed September 7, 2017).

[11] Linus Gustafsson and Magnus Ranstorp, Swedish Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq: An analysis of open-source intelligence and statistical data (Swedish Defence University: Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies (CATS), 2017), http://fhs.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1110355/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed September 7, 2017).

[12] “Suruc massacre: ‘Turkish student’ was suicide bomber,” BBC News, July 22, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-33619043 (accessed September 8, 2017).

[13] “Hollande says Paris attacks an ‘act of war’ by Islamic State group,” France 24, November 15, 2015, www.france24.com/en/20151114-paris-attacks-president-hollande-act-war-islamic-state-group-terrorism-france (accessed September 8, 2017).

[14] Ceylan Yeginsu and Victor Homola, “Istanbul Bomber Entered as a Refugee, Turks Say,” The New York Times, January 13, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/14/world/europe/istanbul-explosion.html (accessed September 8, 2017).

[15] “ISIS supporters claim group responsible for Brussels attacks: ‘We have come to you with slaughter’,” Independent, March 22, 2016, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/isis-supporters-claim-responsibility-for-brussels-attacks-bombings-belgium-airpo... (accessed September 8, 2017).

[16] “2015 Year in Review,” Facebook Newsroom, December 9, 2015, http://newsroom.fb.com/news/2015/12/2015-year-in-review/ (accessed January 24, 2016).

[17] “Facebook’s 2016 Year in Review,” Facebook Newsroom, December 8, 2016, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2016/12/facebook-2016-year-in-review/ (accessed September 8, 2017).

[18] Jacob Poushter and Dorothy Manevich, “Globally, People Point to ISIS and Climate Change as Leading Security Threats” (Pew Research Center, 1 August 2017), http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/08/01/globally-people-point-to-isis-and-climate-change-as-leading-security-threats/ (accessed September 5, 2017).

[19] Cole Bunzel, From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State, The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World, Analysis Paper No. 19, (Brookings: Center for Middle East Policy, March 2015), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/The-ideology-of-the-Islamic-State.pdf (accessed September 8, 2017).

[20] Spillover might be also caused by other variables such as terrorist narratives, social media images and discussions created by other entities other than the ISIS. However, this model assumes FFs as the key spillover agents and pays special attention to them.

[21] Jerry W. Wright and Laura Drake, eds., Economic and Political Impediments to Middle East Peace: Critical Questions and Alternative Scenarios (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2000).

[22] Etel Solingen, “Transcending disciplinary divide/s,” in International Relations Theory and a Changing Middle East, Project on Middle East Political Science Studies, September 17, 2015, http://pomeps.org/2015/09/17/international-relations-theory-and-a-new-middle-east/ (accessed November 1, 2015).

[23] Curtis R. Ryan, “Regime Security and Shifting Alliances in the Middle East,” in International Relations Theory and a Changing Middle East, POMEPS Studies 16 (Aarhus University, September 2015), 42-46.

[24] Bassel F. Salloukh, Syria and Lebanon: A Brotherhood Transformed, Middle East Report No. 236 (Middle East Research and Information Project, 2005), http://www.merip.org/mer/mer236/syria-lebanon-brotherhood-transformed (accessed September 8, 2017).

[25] Brian Michael Jenkins, How the Current Conflicts Are Shaping the Future of Syria and Iraq (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2015), http://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE163.html (accessed September 8, 2015.)

[26] Daniel Byman, “Beyond Iraq and Syria: ISIS’ ability to conduct attacks abroad,” Brookings, June 8, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/beyond-iraq-and-syria-isis-ability-to-conduct-attacks-abroad/ (accessed September 8, 2017).

[27] I am aware of the fact that this type of conclusion will be more accurate after analyzing extensive data and examining key political security developments and their impacts on subsequent events. However, considering the space limitations for this article, a short and rough analysis for 2015 and 2016 is provided.

[28] Bunzel, From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State, 13.

[29] Charles C. Caris and Samuel Reynolds, ISIS Governance in Syria, Middle East Security Report 22 (Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of War, July 2014), http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/ISIS_Governance.pdf (accessed September 7, 2017)

[30] Richard Barrett, Foreign Fighters in Syria (New York: The Soufan Group, June 2014), http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/TSG-Foreign-Fighters-in-Syria.pdf (accessed November 23, 2016).

[31] Foreign Fighters: An Updated Assessment of the Flow of Foreign Fighters into Syria and Iraq (New York: The Soufan Group, December 2015), http://soufangroup.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/12/TSG_ForeignFightersUpdate3.pdf (accessed January 23, 2016).

[32] Joshua Meservey, “Al Shabab’s Lessons for ISIS: What the Fight Against the Somali Group Means for the Middle East,” Foreign Affairs, January 24, 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ethiopia/2016-01-24/al-shababs-lessons-isis(accessed January 26, 2016).

[33] Anne Speckhard and Ahmet S. Yayla, “Eyewitness Accounts from Recent Defectors from Islamic State: Why They Joined, What They Saw, Why They Quit,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 6 (December 2015): 95-118.

- 29986 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML